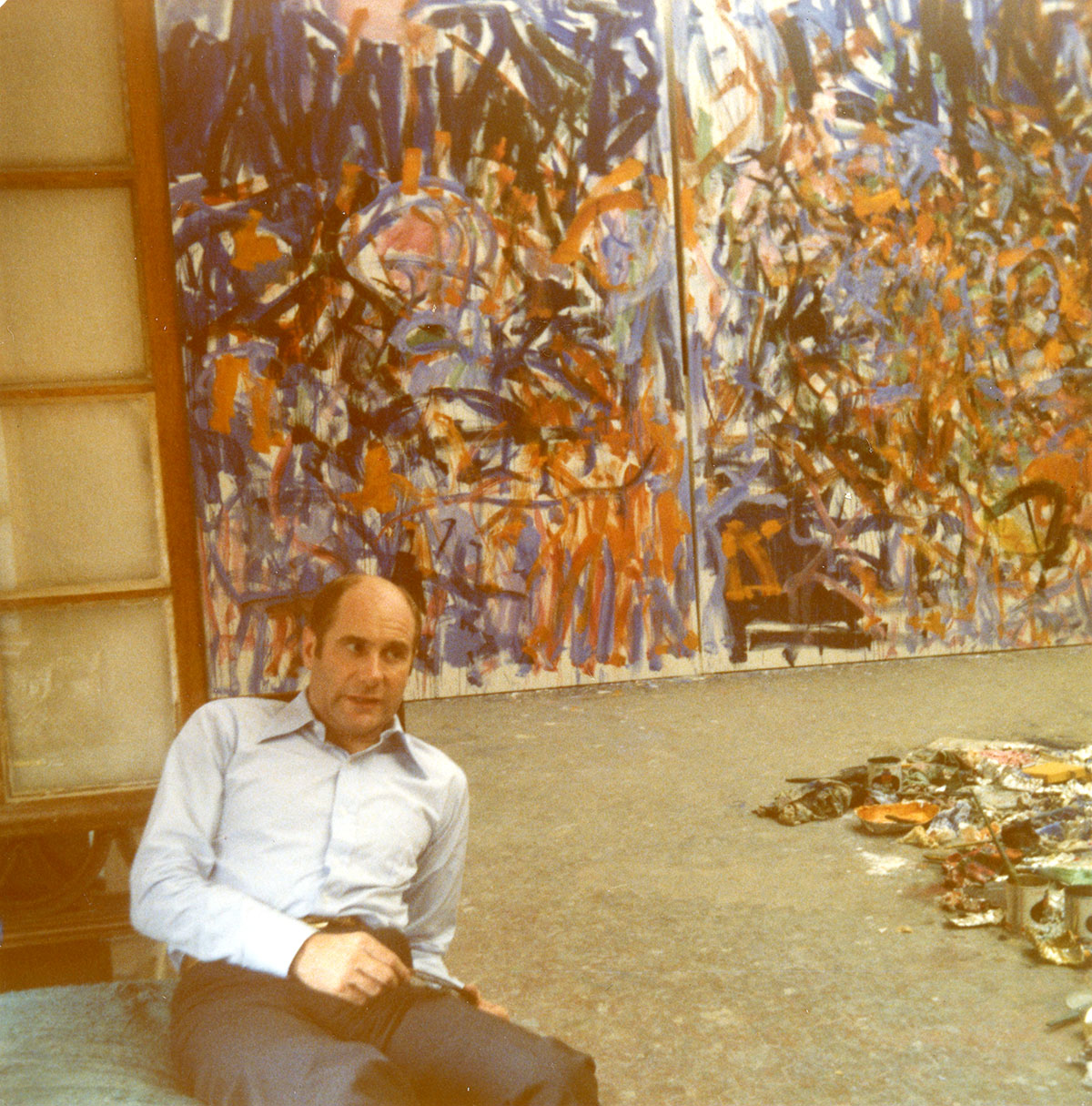

When Xavier Fourcade visited Joan Mitchell at La Tour in June 1976 to lay the groundwork for her exhibition at his New York gallery that fall, Weeds was well underway but not quite finished, as a photograph of Fourcade in Mitchell’s studio attests: the painting leans against the wall behind him, its two panels pushed together.

Compare Weeds as it appears in the photograph to the completed work. The left panel was already covered top and bottom with vertical strokes—“those seductive pawmarks,” one critic would call them at Fourcade—though a rosy clearing near the panel’s center would soon be worked over.1 Search for this patch of pink in the completed painting and find it glowing beneath a diagonal procession of arcing blue forms—trusses, branches, legs with feet—tunneling in nearly linear perspective. Traipsing down and to the right, the color blue leaps the boundary between panels and pools underneath an orange triangle. These adjustments, made between Fourcade’s visit and the work’s completion, built momentum, a lateral choreography that propels the composition from left to right.

Yet Mitchell also worked to disrupt this trajectory, calibrating tension at the interstice where the two panels meet. Orange vertical marks alternate on either side of the gap. Some she laid down before the photograph was taken, but others she added, tightening their relation to one another. Notice a wide orange mark at bottom right, parallel to the floating triangle, and a knife-thin one at center left. They firm up the boundary between the two panels, reinforcing their separateness while at the same time making an event of their proximity. The right panel compresses toward its side of this shimmering gap with roiling, centripetal energy. Instead of traversing over and across, as on the left, this view presses down and in.

By October, “the blue and orange diptych” was finished and shipped to New York ahead of the November opening.2 The title Weeds first appears in Mitchell’s list for the show’s catalogue, along with Straw and Clinging Vine, titles that corroborated critics’ observations that the artist’s new body of work burgeoned with plantlike energy, “the effect of leaves and stems, of something growing.”3 Weeds was characteristic of this quality, even if it was more “frenetic” than the other works, an outlier for its blazing blue and orange palette.4 The painting would be acquired out of the Fourcade show by Joseph Hirshhorn for the newly opened Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C.

The title Weeds does not delimit Mitchell’s subject so much as spur associations that work together with the visual experience to elicit a feeling. Weeds are wayward plants, bursting from the earth and spreading out with hardy indifference to human plans. Keeping weeds in check is a disciplined practice, a job that is never done. Yet gardeners recognize it as necessary and constructive, since weeds can hinder desired plants and break apart pathways and steps. To weed is to impose limits, to constrain some elements such that others may flourish.

The struggle with weeding, as with painting, is to determine what is vibrant, desirable, and what must be brought under control.

What counts as a weed, however, is all about context and preference. Many of Mitchell’s favorite trees and flowers were weedlike: wild oaks, honeysuckle, daisies. Sunflowers became a recurring subject in her work after their “seeds flew around” and astonished her gardener by springing up “in unexpected places.”5 It is easy to imagine Mitchell admiring, even identifying with such resilient forms of life—beautiful in their toughness, untethered by discriminative social categories that would dictate where and how they should root themselves in the world.

With multiple gardens surrounding her home and studio, weeding was a routine part of life at La Tour. Notes left by Mitchell for visitors in these years, often written over nights of painting, frequently enlisted them to help with various chores, including caring for the garden. “Got your weeds through the gate,” she wrote early one summer morning in 1976 to Patricia Molloy, who was visiting from New York. “Could you not ‘dead head’ roses.”6

Like painting on a large scale, weeding is full-bodied work. Plants are yanked from the ground and piled up. Stems, leaves, and roots tangle, their linear forms clinging into a volume. Wrap your arms around this bundle and smell the wet heat of decomposition already underway. Allowed to live, weeds luxuriate—they thicken and spring forth, always finding new ways to grow. Like paint, weeds drip; Mitchell’s close friend the composer Gisèle Barreau described Weeds as “herbes jaillissantes” (gushing weeds), capturing this shared liquidity.7 Reviewing the Fourcade show, critic Ann Sargent Wooster recognized such tactile proximity as the viewpoint of Mitchell’s new paintings, “as if one were not observing nature but pressing one’s face into it.”8

The struggle with weeding, as with painting, is to determine what is vibrant, desirable, and what must be brought under control. In Weeds, Mitchell explored the potential benefits of rigorously observed constraints. She restricted her palette to complementary blue and orange, with pink and green in a secondary role; these colors intensify when paired. She controlled her brushwork; vertical strokes demarcate oval areas that pulsate with petallike dabs. She reinforced the parameters of each panel, drawing out a dueling, oppositional dynamic in the diptych format while using color and line to span the whole. By compounding constraints—keeping color, mark, and format in check—Mitchell heightened the impact of each, resulting in a painting that bursts with weedlike energy, as if unconstrained by its own spatial boundaries. Mitchell would reprise the theme of weeds in several print series completed at Tyler Graphics in the final month of her life. These prints distill the mechanics of Weeds on a much smaller scale and with graphic clarity, this time by means of a three-color layering process.

There again, Mitchell shows the discipline it takes to keep the visual field alive. Out of a tangled mass, a wayward line approaches a boundary and leaps the gap to another sheet.

Joan Mitchell closes August 14, 2022. Purchase tickets at artbma.org.

Notes

1. John Russell, “Joan Mitchell,” New York Times, December 3, 1976.

2. Letter from Xavier Fourcade to Mitchell, October 8, 1976, Fourcade Archives.

3. Letter from Mitchell to Fourcade, October 19, 1976, Fourcade Archives. Phil Patton,“Reviews. New York: Joan Mitchell,” Artforum 15 (February 1977): 71–72.

4. Allen Ellenzweig, “Joan Mitchell, Xavier Fourcade,” Arts 51, no. 6 (February 1977): 22.

5. Letter from Mitchell to Patricia Molloy, September 1, 1969, JMFA008.

6. Note from Mitchell to Molloy, n.d. [ca. September 1976], JMFA008.

7. Gisèle Barreau, “Porte adieu, Joan Mitchell, souvenirs,” in Joan Mitchell: la pittura dei due mondi/la peinture des deux mondes (Milan: Skira, 2009), 140.

8. Ann Sargent Wooster, “New York Reviews: Joan Mitchell,” Art News 76 (February 1977): 125–26.