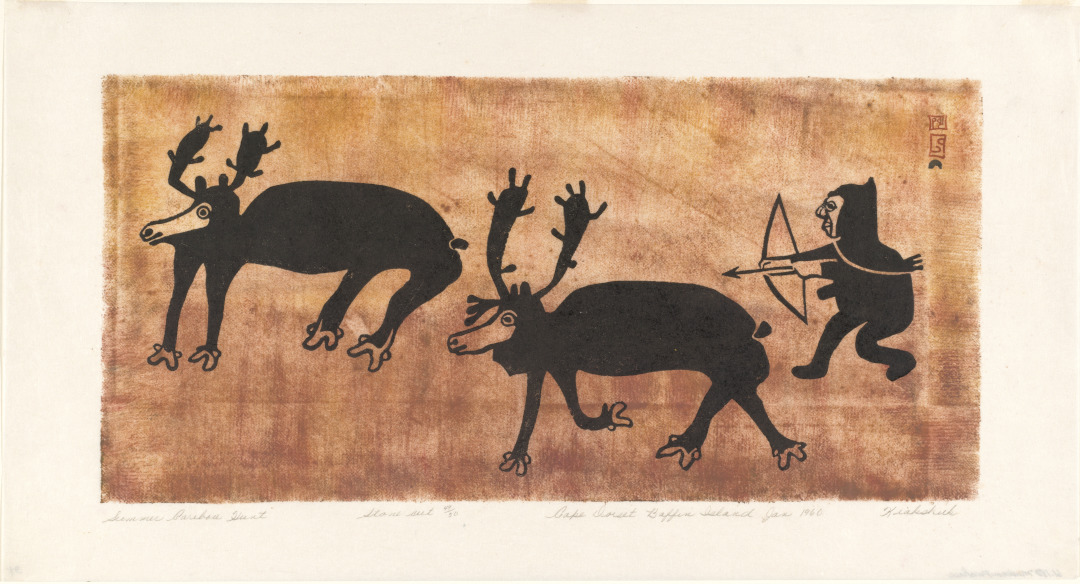

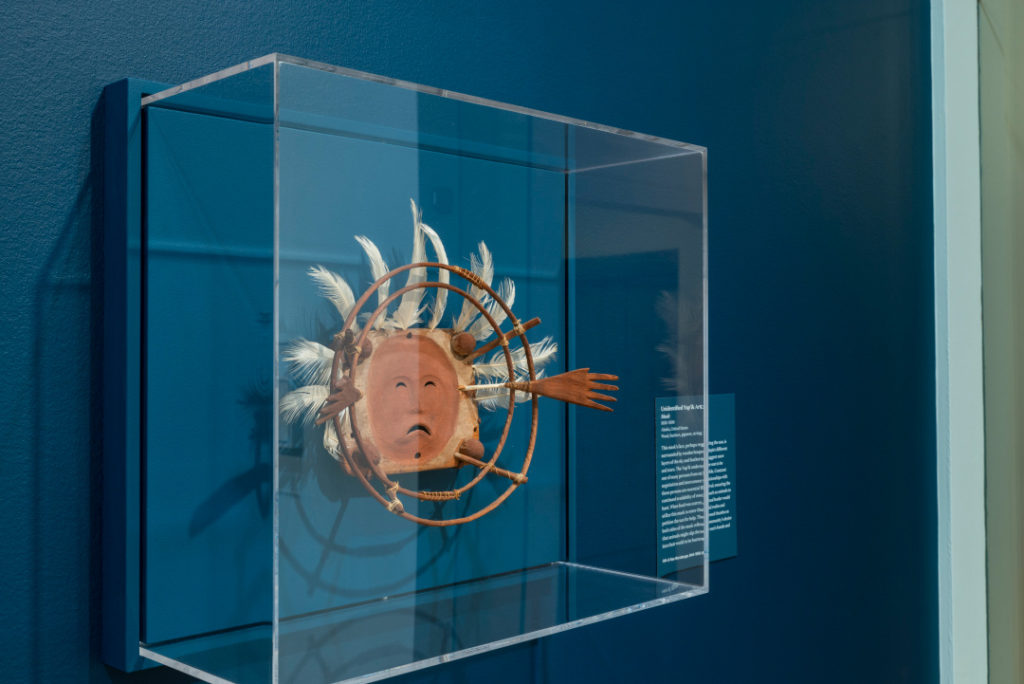

The stone-cut prints[1] of Inuit hunting scenes—Searching for Seal Holes by Innukjuakju Pudlat and Kiakshuk’s Summer Caribou—stand out immediately in Artic Artistry, an exhibition of mostly small sculptures and functional objects by Greenlandic, Alaskan, and Inuit artists. Made in 1960, Searching for Seal Holes and Summer Caribou represent a key moment in Inuit art history when artists making work for the outside market turned from stone-carvings to stone-cut prints. Their entrance into the art market brought about a shift in some southern Canadians’ perceptions of Inuit work, from that of craft production to that of fine art[2]. The prints highlight the history and traditions of Inuit artists[3], who often depicted everyday hunting scenes, but also the influence of the midcentury tastes of southern Canadians and of one man in particular, James Houston.

An artist and employee of the Canadian government, Houston created the western market demand that still exists today for Inuit art[4]. An unreliable narrator who bent reality to play to his western audience’s prejudices, Houston functioned as a broker between Inuit artists and southern Canadian collectors. His task, assigned to him in the early 1950s by the Canadian Handicrafts Guild, the Canadian government, and the Hudson Bay company was to develop a Native arts program on Baffin Island’s Cape Dorset to provide economic relief to Inuit artists[5]. Purchasing an assortment of commissioned works that included small soapstone carvings and other traditional crafts directly from Inuit artists and writing promotional pamphlets exotifying their culture, Houston fabricated the distance between the Inuit community and southern Canadians[6]. With his writing, Houston located the Inuit in an imagined ahistorical reality, what critic Mary Louise Pratt has called the “timeless present tense.”[7]

In the late 1950s, in what was then Cape Dorset, Houston and the Inuit artists he worked with shifted their focus to printmaking, in which Houston saw great market potential. In 1958, Houston went to Japan to learn printmaking from Un’ichi Hiratsuka, an artist who worked in the sósaku hanaga style, which emphasized the artist’s hand in creating the woodblock prints, a departure from the tradition of artists outsourcing the plate-making process[8]. He brought this method back and asked his Inuit collaborators to create drawings that could be turned into stone-carved prints. Houston’s big idea was marketing the Inuit within the context of modernism, skillfully making Inuit art both “other” and familiar to his audience who had some prior knowledge of Japanese prints and modern art techniques[9] [10].

Printmaking was entirely new to the Arctic, which presented a problem for Houston, who had implied that the soapstone sculptures he had previously sold to his southern Canadian audience, were a continuation of an age-old tradition[11]. Additionally, printmaking is a multi-step process that requires careful planning on the part of the artist, a reality that contrasts with Houston’s previous assertions that Inuit artists work intuitively[12]. He circumvented these narrative challenges by assuring his readers that the Inuit were progressing to using this new-to-them technology in artmaking while maintaining their own way of life[13]. The pejorative tone of Houston’s writings resonated with the audience of southern Canadians they were intended for and motivated sales. The influence of Houston’s Euro-Canadian modern art concepts ensured the work was palatable for mid-twentieth century Qallunaat (non-Inuit) buyers.

Early on, Houston realized that the Southern Canadians were interested in unique rather than replicated works so limiting print releases was key when the collective shifted to printmaking[14]. While developing the first print release in 1959, Houston, his colleagues, and the Inuit artists decided that only a small percentage of Inuit drawings would be turned into prints[15]. The practice of limiting the number of designs available each year, as well as the total number of prints made, continues today and has protected the demand for Inuit art.

Both Innukjuakju Pudlat and Kiakshuk were associated with Houston’s Cape Dorset print collective, if only for a short while. Kiakshuk, who had been known as an excellent hunter in his youth, worked with Houston for six years from 1960 to his death in 1966, producing 52 prints for the co-operative in that short amount of time. His works are in museum collections throughout the United States and Canada and several members of his family have carried on the artistic tradition since his death. Innukjuakju Pudlat was married to another co-operative artist, Pudlo Pudlat, and began drawing when her husband suffered an arm injury that made it difficult for him to produce work. She was an active contributor to the collective from 1959 until she became ill in 1970. Her work is also internationally recognized[16].

The BMA’s Inuit art collection offers insight into the Kinngait Co-operative[17], an artistic community that continues to thrive today producing an annual print series and selling works in their Toronto, Ontario gallery Dorset Fine Arts. Thanks to the high percentage of artists who continue to live and work in Kinngait, it was named the most artistic Canadian municipality in 2006[18].

Arctic Artistry is curated by Darienne Turner, Assistant Curator for Indigenous Art of the Americas.

This exhibition is generously supported by Kwame Webb and Kathryn Bradley and the Jean and Allan Berman Textile Endowment Fund.

Notes

[1] “Stonecut is an elegant process and Cape Dorset printmakers have refined it to a fine art. The first step is tracing the original drawing and applying it to the smooth surface of the prepared stone. Using india ink, the stonecutter delineates the drawing on the stone and then cuts away the areas that are not to appear in print, leaving the uncut areas raised, or in relief. The raised area is inked using rollers and then a thin sheet of paper – usually fine, handmade Japanese paper – is placed over the inked surface. A protective sheet of tissue is placed over this sheet, and the paper is pressed gently against the stone by hand with a small, padded disc. Only one print can be pulled from each inking of the stone, so the edition takes time and patience and care.” Dorset Fine Arts: https://www.dorsetfinearts.com/stonecut, accessed November 3, 2022.

[2] Heather Igloliorite, “Hooked Forever on Primitive Peoples: James Houston and the Transformation of “Eskimo Handicrafts” into Inuit Art”, Mapping Modernism, Ed., Elizabeth Harney and Ruth B. Phillips, Duke University Press, 2019, 62-90, “The initial shift from a general purview of Inuit expression to the focused fine-art production of stone sculptures, then prints and eventually drawings, undeniably succeeded in firmly cementing a clear division between Inuit “high” fine arts and “low” craft productions that persisted in the field for decades. […] The early success of Inuit art in the South has relied on its separation from craft and its transition from miniature ivories and souvenirs to fine art genres of large stone carvings, wall hangings, drawings, and prints; today this has grown to include such contemporary modes of production as painting, photography and installation” (Igloliorite 84).

[3] Reviewing Searching for Seal and Summer Caribou Inuk curator and anthropologist Krista Ulujuk Zawadski explains, these prints “do a good job of documenting Inuit life […] These are still scenes that happen today, but this offers a sense of nostalgia. This is what my ancestors did, and we still do it today.” Caribou remains a central aspect of Inuit livelihood, providing food and skins for clothing that can withstand freezing temperatures. Zawadskiexplains that in 2022, “it costs a lot to live in the Arctic, people prefer to go out hunting rather than go buy overpriced meat at the store.” In addition to its importance as a source of food and warmth, caribou is used to describe months in the Inuit calendar, including “the one when the antlers fall off” which corresponds to December. Climate change and industry have impacted the herds and in some parts of the Arctic, such as Kinngait where these prints were made only 80 years ago, the caribou are nearing extinction.

[4] Kristin K. Potter, “James Houston, Armchair Tourism and the Marketing of Inuit Art”, Native American Art in the Twentieth Century, Makers, Meanings, Histories, Ed. W. Jackson Rushing III, Routledge:1999, 39-55.

[5] By the 1940s the Canadian government could no longer ignore the “extreme poverty and cultural displacement of the Inuit” brought on by “increased contact with the southern world” which introduced new problems without the social safety net offered to other groups. (Potter 39).

[6] (Potter 43).

[7] (Igloliorite 79).

[8] Courtney R. Thompson, “Inuit Prints, Japanese Inspiration: Early Printmaking in the Canadian Arctic”, Art in Print, September-October 2012, 32-34. (Thompson 32).

[9] As Thompson, explores, Houston was a powerhouse at using “the context of modernism and [his perception of] a natural symbiosis between the abstracted forms and figures of Inuit art and the properties of Japanese printmaking” (Thompson 32-3)

[10] Houston’s pamphlets did not tell readers how to buy Inuit art, instead, he focused on its rarity and craftsmanship. “Once it became commonly understood that Inuit art was not easily acquired, the desire for it became an even more culturally sanctioned quest— a quest which continues to drive the Inuit art market today” (Potter 44)

[11] “Houston promoted Inuit artists as Savage Savants—learned yet untaught— who have a quasi-religious obsession with craftsmanship and are so-well versed in their aesthetic standards that they make judgments in absolute unison […] His essays allowed him to promote this mirage of cultural purity in which the Inuit survive in full bloom relatively unaffected by their patrons. Fortunately, however, this interaction did profoundly affect the Inuit in that it provided economic relief and facilitated cultural and artistic recognition” (Potter 48).

[12] According to Houston, for the Inuit, “art-making is not an intellectual activity […] but a purely natural initiative one” (Potter 48).

[13] Houston told his readers the Inuit were “on the threshold of cultural metamorphosis” which satisfied them that “while the Inuit are beginning to utilize technology in their creation of art, they remain firmly grounded in their “primitive” background” (Potter 51).

[14] Houston explained in his publication, “Eskimo Handicrafts: A Private Guide for the Hudson Bay Company Manager, 1953,” ‘Function objects… have been our poorest selling items. This is because our Agents and customers are looking for primitive [sic] work by a primitive people. This term primitive does not mean that the work is crude since many primitive people have made extremely delicate crafts, but it is true that the ash tray, pen holder and cribbage board do not represent the Eskimo culture and as a result, there is little interest in buying that type of work” (Potter 45).

[15] “Since 1959, out of almost one hundred thousand drawings, only one thousand have been translated into prints […] reflecting a rigorous system of acceptance and rejection” (Potter 49).

[16] Biographical information on the artists is from https://nativecanadianarts.com/ and https://www.inuitartfoundation.org/

[17] Also known as the West Baffin Eskimo Co-Operative

[18] CBC Canada, February 13, 2006: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/cape-dorset-named-most-artistic-municipality-1.574437, accessed October 3rd, 2022.