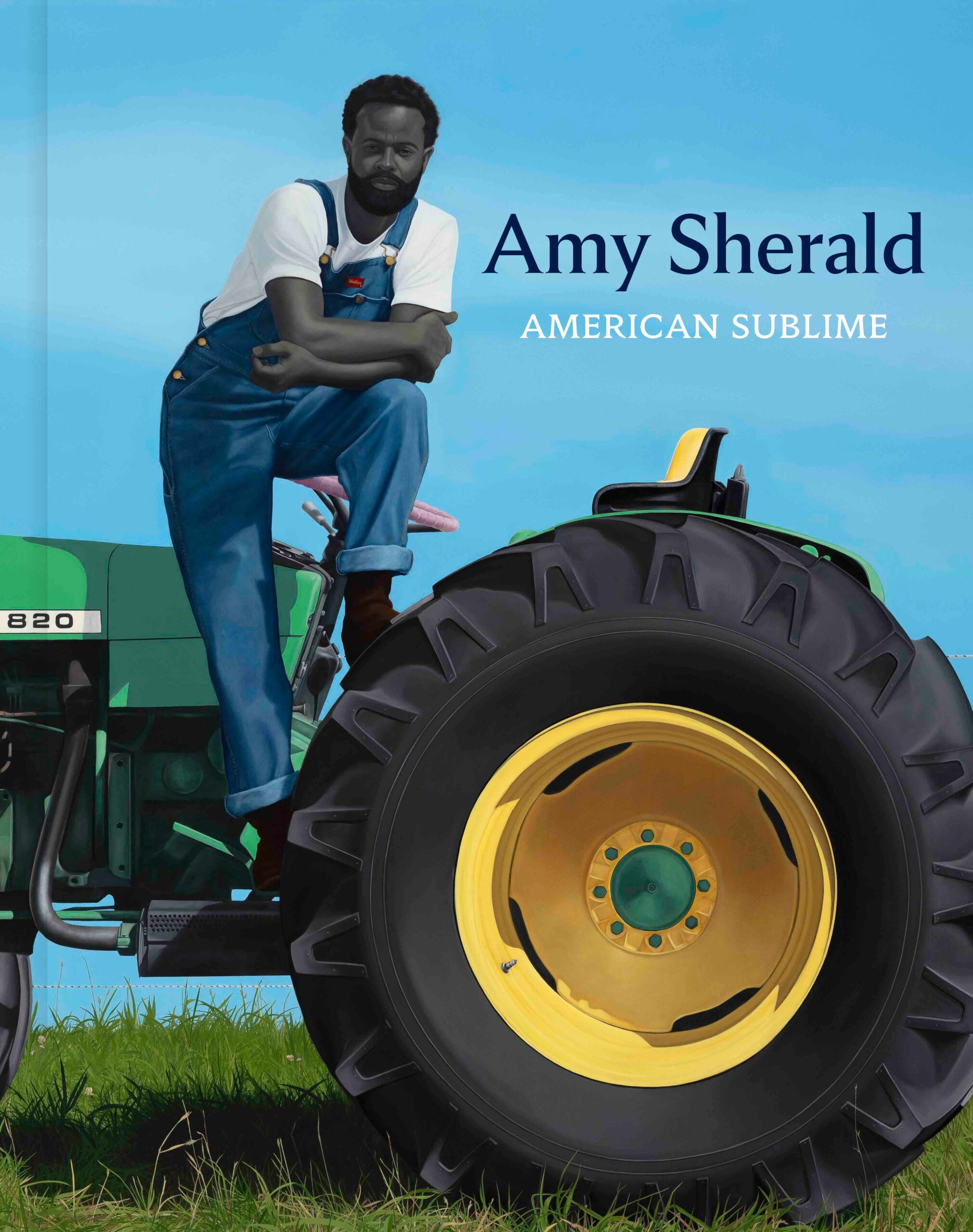

On November 2, 2025, the Baltimore Museum of Art opened Amy Sherald: American Sublime. The acclaimed exhibition is the most comprehensive presentation of Sherald’s work to date, illuminating the arc of her career from 2007 to 2024 through approximately 40 paintings. From foundational early works to some of her most iconic and recognizable portraits and rarely seen examples, American Sublime captures the power and poignancy of Sherald’s artistry and traces her ascendance as one of the most influential figurative painters of our time. The exhibition will remain on view in Baltimore through April 5, 2026.

Accompanying the exhibition is a fully illustrated catalog, which has been hailed by the New York Times Book Review as one of its 10 Giftworthy Visual Books and described by Apollo as “sublime, indeed.” In the excerpt below, curator and volume editor Sarah Roberts sheds light on Sherald’s work and the exhibition’s—and book’s—title.

Amy Sherald’s American Sublime

Amy Sherald’s paintings speak of the American present. Her works herald and exalt the complexity of each person she summons in paint, creating a world of each one and inviting us in. While these depictions must be understood within the context of centuries of violence against and negation of Black people in the United States, Sherald offers them as a counter-representation of Black life, one that speculates, What if? What if we hold all this history and conjure an entirely different vision of the present, one that is not circumscribed by historical narratives around race? What if the abundant humanity of every individual is a given, honored without qualification or preconception? The resulting paintings present a vision of Black Americans just being in this world, not in contention, not racialized, but simply living lives of richness, rightness, and greatness in their ordinariness. Both deeply rooted in and critical of American myths and ideals of freedom, beauty, ambition, and expansiveness, Sherald’s body of work stems from her certainty about the power of art to induce emotion, create human connection, and spur personal and social change. She paints a better world by bringing our attention to the fact that it already exists in the tilt of a head, the air of a gaze, the fold of a hand. Such details convey the multitudes held within each of her subjects—these depictions grow out of individual experience and reach outward to engage with Black American culture, the American collective imagination, and history writ large. In this, Sherald’s paintings offer nothing short of a new, transcendent vision of contemporary American life. An American sublime.

Sherald had the title of this book and the exhibition it accompanies in mind for some ten years before the project became concrete. The idea of the sublime has traveled in and out of Western art history since the mid-eighteenth century, and it offers a thought-provoking frame for considering Sherald’s work. A sinuous concept essentially referring to an experiential state, it emerged as a Romantic notion describing instances of great emotional magnitude, ranging from terror and awe to boundlessness and spiritual elation, particularly in response to the natural world. The experience of feeling transported by or at one with nature while standing in a magnificent landscape or while looking at a painting that captures such splendor typifies the Romantic sublime.1 In the nineteenth century, painters including Thomas Cole and Thomas Moran in the US, J. M. W. Turner in England, and Caspar David Friedrich in Germany (fig. 1) created works that trumpeted vast, glorious landscapes and underscored the insignificance and vulnerability of humans by comparison. Their Romantic sublime might be described as a sense of feeling overwhelmed and losing oneself in the face of nature, a recognition of the incommensurability of the individual with the broader world. In the US, this genre of painting helped to establish a shared national awe at the immense scale of the American landscape, perpetuate the problematic politics of westward expansion, and promote the mythologization of American individualism.2

Jump forward to the 1940s in the US, the period when American painters began creating enormous abstract canvases and drawing connections between their work and experiences of the vast national geography. Barnett Newman defined the sublime as the feeling of revelation inspired in viewers by his own abstract painting and that of some of his peers, including Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, and Clyfford Still.3 For Newman, this sublime could only have arisen in this country, in response to its physical expanse and in contrast to European painters (he did not look beyond western Europe and the US), whom he saw as blinded by histories of beauty and representation in art. He argued that the American style of abstract painting he espoused met a universal desire for exalted emotional experience by offering self-evident, absorbing images free of references to beauty, history, religion, myth, and the traditions of art. Freed from such conventions, his abstraction centered instead on individualism—the painter’s own mind and sensations. In his 1948 statement “The Sublime Is Now,” he wrote, “Instead of making cathedrals out of Christ, man, or ‘life,’ we are making it [sic] out of ourselves, out of our own feelings.”4 Newman’s American sublime encompasses paintings that capture an individual artist’s emotions and ideas with such directness and authenticity that anyone open enough might feel moved or even identify with the subjective experience they convey. Rather than being cast as insignificant, Newman centers and exalts the individual. He heroizes the painter as the source of the sublime event and assumes the experience of it to be personal rather than collective or communal.

In the early 2000s, critic and curator Okwui Enwezor identified what he termed the “racial sublime” operating in American culture.5 For Enwezor, the racial sublime takes the form of varying combinations of repression, violence, aestheticization, and desire in representations of Black Americans in much of the literature, music, film, mass media, and popular culture produced across US history and into the present. As with other formations of the sublime, both awe and, particularly, terror circulate in Enwezor’s conception. Such representations continually generate an iconography of racial violence and embed knowledge of this violence against Black Americans deep in the social consciousness. The racial sublime he describes is thus uniquely American, pervasive, and a fundamental structure of US culture. In Enwezor’s words, “It is never said enough that nothing escapes the racial sublime and the epistemic violence that surrounds it in American civilization.”6 He argues that artists Glenn Ligon, Kara Walker, Fred Wilson, and Lorna Simpson take up scrutiny of the racial sublime as a central strategy in their work, plumbing images and language that have perpetuated it to critique and unravel its functions. Thus, a work like Simpson’s Waterbearer (fig. 2), with its text “SHE SAW HIM DISAPPEAR BY THE RIVER, / THEY ASKED HER TO TELL WHAT HAPPENED, / ONLY TO DISCOUNT HER MEMORY.,” can only be understood after first acknowledging the histories of violence that necessarily structure any such attempt. Simpson’s incisive works peel apart the cumulative layers of representation and signification to lay bare suppressed facets of American culture.

Sherald’s paintings also critique this racial sublime, strategically activating imagery associated with ideas of Americanness and American history in order to define a different iconography of race altogether. Often this involves recasting American myths and tropes by enacting them with Black figures in archetypal roles—The Cowboy, The Beauty Queen, The Girl Next Door, The Farmer—making Black American stories The American Story. Crucially, Sherald insists on the possibility of experiencing sublimity and the depth of everyday life through images and stories that point to its wonder and sanctity rather than its traumas. If Newman’s sublime rests in the potential of individual experience to be powerful and affecting for all viewers, Sherald’s arises from her paintings’ potent ability to convey individual, imagined, and collective experiences of Black American life as similarly expansive and impactful for all. She refuses to engage on the field of repression and violence identified by Enwezor, turning instead to a distinctive kind of world-making and magical thinking.

Amy Sherald: American Sublime is organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

This exhibition is curated by Sarah Roberts, former Andrew W. Mellon Curator and Head of Painting and Sculpture at SFMOMA.

The BMA’s presentation is organized by Asma Naeem, Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director; Cecilia Wichmann, Curator and Department Head of Contemporary Art; Antoinette Roberts, Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art; and Dylan Kaleikaumaka Hill, Meyerhoff-Becker Curatorial Fellow.

Amy Sherald: American Sublime is generously supported by the Mellon Foundation.

Major support provided by the Ford Foundation, the Terra Foundation for American Art, and Hauser & Wirth.

Additional support provided by David Imre and Tom Crusse, Amy Elias and Richard Pearlstone/The Pearlstone Family Fund, Amy and Marc Meadows, Robert Meyerhoff and Rheda Becker, Katie Adams Schaeffer, Joanne Gold and Andrew Stern, Frederick Singley Koontz, Pat Lasher and Richard Jacobs, John Meyerhoff, M.D. and Lenel Srochi Meyerhoff, George Petrocheilos and Diamantis Xylas, and The Aaron Straus and Lillie Straus Foundation.

- The Romantic sublime derives, of course, from the well-known aesthetics of Edmund Burke, particularly his A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1863). Burke’s writings have been dissected extensively in relationship to twentieth-century art and Barnett Newman’s ideas of the sublime, as well as related texts by Robert Rosenblum and Jean-François Lyotard. The latter three authors’ writings, as well as many other considerations of the sublime, are usefully collected in Simon Morley, ed., The Sublime (London: Whitechapel Gallery; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010). ↩︎

- On pages 32–37 in this volume, Elizabeth Alexander further discusses the ways these types of paintings in the US were intertwined with the doctrine of westward expansion and how they disregarded the enslaved labor and displacement of Native peoples involved in accomplishing that movement. Also inherent in such paintings is American mythologizing of the individual, in the form of the implied bravery, self-sufficiency, and perseverance of those who undertook exploration of the West. ↩︎

- Barnett Newman, “The Sublime Is Now,” part of “The Ides of Art: 6 Opinions on What Is Sublime in Art?,” Tiger’s Eye 1, no. 6 (December 1948): 51–53. ↩︎

- Ibid., 53. ↩︎

- Okwui Enwezor, “Repetition and Differentiation: Lorna Simpson’s Iconography of the Racial Sublime,” in Lorna Simpson (New York: Harry N. Abrams, in association with the American Federation of Arts, 2006), 103–31. ↩︎

- Ibid., 113. ↩︎