One of the first Japanese American servicemen detained in the wake of Pearl Harbor drew on personal experience to develop his work outside of formal training

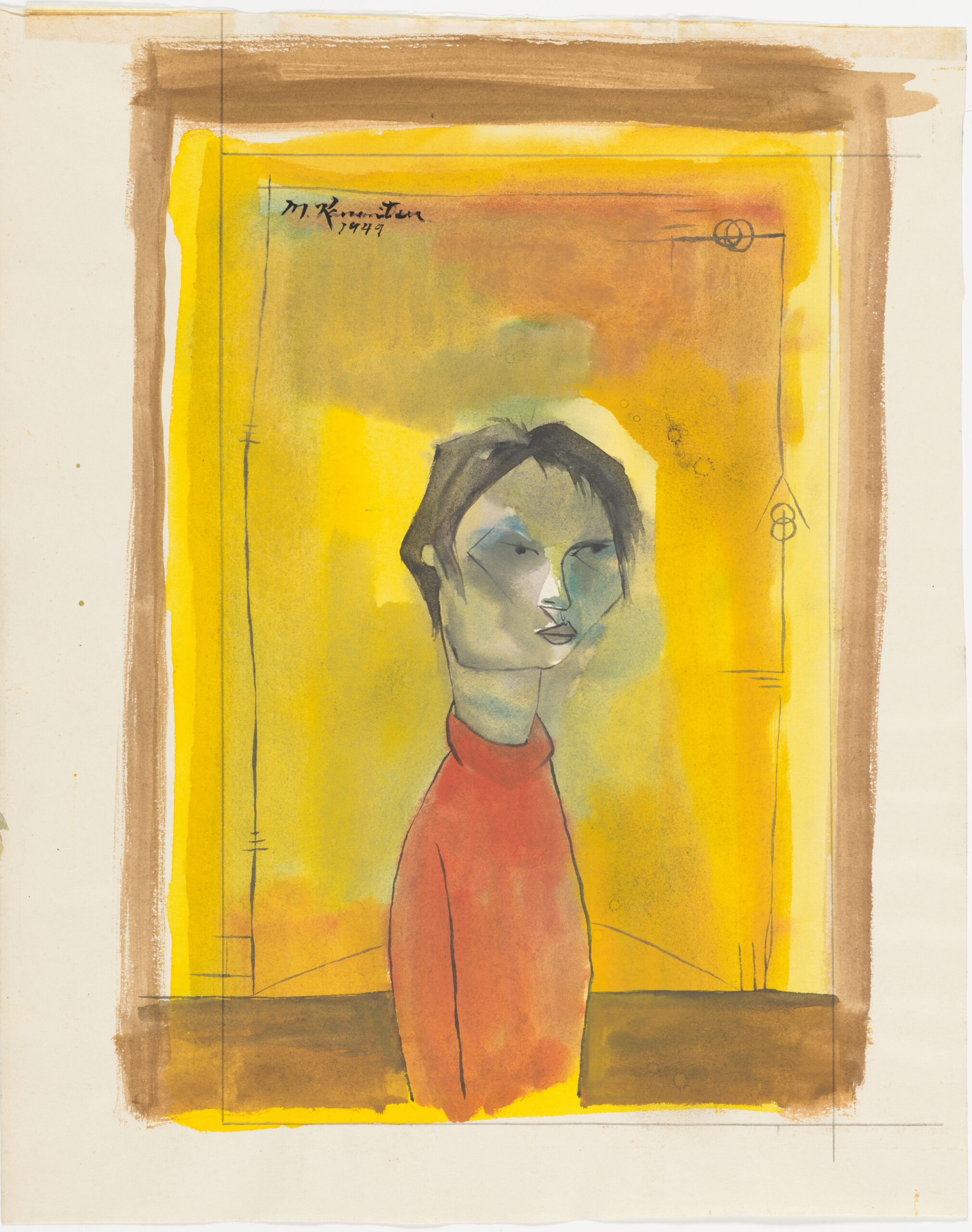

Few people are aware that West Coast abstract artist and influential college educator Matsumi Kanemitsu (1922-1992), or Mike as he was known to his friends, spent his formative years in Baltimore. It’s this brief but creatively significant time from 1947 to 1954 that the new BMA exhibition Matsumi Kanemitsu: Figure and Fantasy chronicles. The exhibition’s 58 works have been a part of the museum’s collection since art collector and major Kanemitsu supporter Blankfard Martenet (1898–1957) donated them in the 1950s. Most of the pieces in this exhibition are on display for the first time.

Kanemitsu traveled to opposite ends of the globe during childhood. He spent time in the countryside outside of Hiroshima, Japan, where his grandparents lived and the climate was thought to be better when he was sick, and in Ogden, Utah, a railroad town where he was born. Those years moving between hemispheres foreshadowed the artist’s subsequent life of world travel.

In 1940, upon returning to the United States from Japan due to rising militarism and family discord, Kanemitsu’s Japanese heritage became a source of conflict as well as belonging. The artist spoke with a foreign accent in both Japanese and English and was often treated as an outsider to both cultures. During this time, Kanemitsu hitchhiked throughout the American West, finding work in a copper mine in Nevada and spending weekends drawing nudes at a brothel for $5 apiece.

In June of 1941, after leaving Japan only seven months prior, he enlisted as a U.S. citizen as an infantry trainee in the U.S. Army. In December of that year, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Kanemitsu was one of many Japanese American servicemen placed under military detention. Eventually, he was allowed to spend the rest of the war following artistic pursuits related to but not necessarily assigned by the army. He began making camouflage illustrations and creating informational signs and posters. On the side, he also drew officers’ wives. Many of the drawings that he created after World War II reflect the mental strain and isolation he experienced during wartime. Leslie Cozzi, Curator of Prints, Drawings & Photographs, says of Kanemitsu’s time in the military, “He’s treated with a lot of xenophobia and he’s subject to a lot of discrimination, but at the same time, he formally becomes an artist.” Kanemitsu’s first solo exhibition was at Fort Riley, Kansas during the war, using supplies provided by the Red Cross. It was also during his military service that he traveled to Europe and became familiar with the works of Pablo Picasso, Francis Bacon, and Henri Matisse.

This exhibition is a case study for how an artist can draw upon their personal experiences to develop their work outside of a school environment.

At the conclusion of the war, the artist moved to Baltimore and married Baltimorean Mildred Hunt. Living in an apartment in the Mt. Vernon neighborhood, working at Bethlehem Steel, and studying masonry and brick laying at a trade school down by the harbor, Kanemitsu created the majority of works in Figure and Fantasy. At the time he drew many of the works currently on display in The Nancy Dorman and Stanley Mazaroff Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Kanemitsu’s training was informal, outside of art school. This exhibition is a case study for how an artist can draw upon their personal experiences to develop their work outside of a school environment.

Greatly impacted by his experiences during WWII and his upbringing split between the United States and Japan, the pieces in the exhibition show an artist observing and inventing, melding his personal history with the beginnings of abstract and surreal experimentations. Cozzi says of the works, “There’s this interesting mix of invention, but also of dealing with and processing the struggle of the everyday mental strain of the war, coupled with the isolation of being treated as an outsider despite being an American citizen.” For the artist, drawing is clearly a way to process what language cannot.

While Kanemitsu only lived in Baltimore for a very short period in his twenties, that experience was foundational to everything that followed artistically for him. Cozzi thinks of the artist as a “chameleon, somebody who was forced to adapt to a lot of change” throughout his lifetime. The works on display show an artist experimenting, trying out a variety of drawing media and styles, and seeing what works for him. We are able to see that prior to moving to New York and being exposed to the work that was developing there in the 1950s, abstraction was not his default mode of expression. Instead, in these works Cozzi points out, “His experience of America and his experience of the era was very particular. He was working through all the options.”

In 1950, Kanemitsu began studies at the Arts Student League in New York with Yasuo Kuniyoshi, who had recently been the first living artist to be granted a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. With Kanemitsu’s marriage to Hunt dissolved, he moved to New York, returning to Baltimore only periodically, including in 1954 for his small solo show at the BMA, which was arranged by Blankfard Martenet. Experiencing housing insecurity upon his arrival in New York, Kanemitsu destroyed or discarded most of the early paintings and sculptures in his possession. The drawings Martenet donated to the BMA are the most extensive record of his origins as an artist.

Matsumi Kanemitsu: Figure and Fantasy is organized by Leslie Cozzi, Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, and on view until October 8, 2023 in The Nancy Dorman and Stanley Mazaroff Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings and Photographs.

This exhibition is supported by Kwame Webb and Kathryn Bradley.