This Gitenga mask caused great excitement when it came to the BMA’s conservation lab for treatment, as the object is impressive both in size (33 ½ x 35 ½ x 19 inches) and in presence.

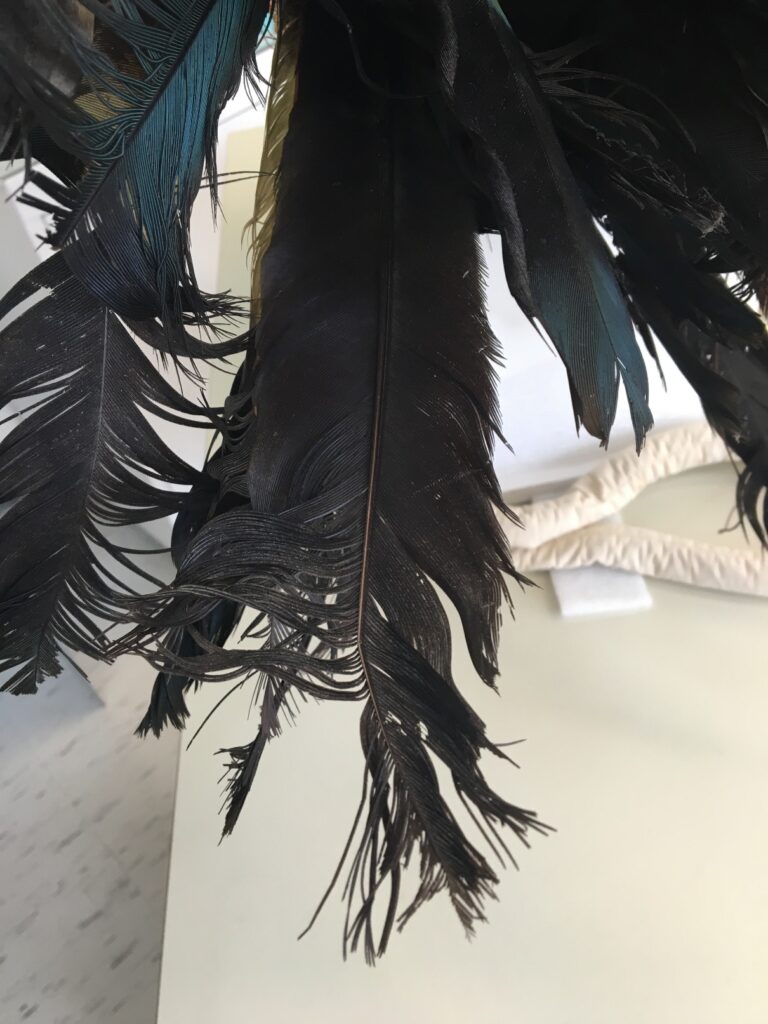

But upon taking a closer look, conservators could see that the majority of the feathers, especially in the back, were deformed and covered in layers of dust and insect remains. Some feathers were bent and broken; in many cases, the “tip” (rachis and barbs) was missing, especially around the mask’s base on the back and left-hand side. It was a very intimidating treatment prospect—and one that would take hundreds of hours to complete before the mask could go on view.

Some interesting discoveries emerged before and during the treatment of this remarkable mask.

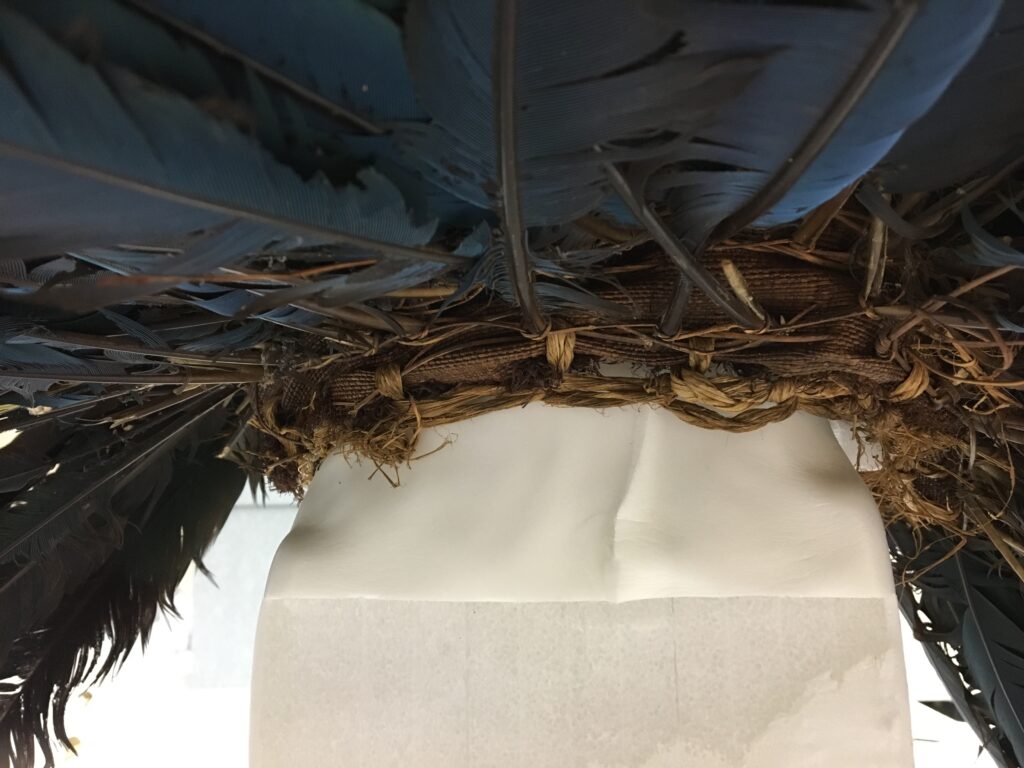

The slow removal of the dust on the back of the mask revealed layers of striking blue feathers. Kevin Tervala, the Eddie C. and C. Sylvia Brown Chief Curator, researched the various birds native to the Pende region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where the mask originates, and discovered that the feathers are from a bird called the Great Blue Turaco.

The feathers were attached to the mask during its construction in a clever way. The feather “base” (calamus or hollow shaft) was bent and inserted into a woven twine support. A second piece of twine was passed through the bent bases of several feathers to create a “string” of them. These strings of feathers were then sewn onto the fabric head cap in layers.

The beautiful neckline of the mask and a section of the back also show how the feathers have been secured to the head cap. Notice all the missing feather tips!

One of the most satisfying discoveries a conservator can make is finding old repairs; in that respect, this mask certainly didn’t disappoint! Someone had carefully taken the top (vane) of a broken feather and adhered it to the remaining base of another broken feather that was missing its tip. In other words: ours was not the first conservation treatment campaign for the mask, and it certainly will not be the last.

In the case of ethnographic works with organic components, conservators must look for evidence that the piece has been treated with pesticides, as some of them contain heavy metals (e.g., mercury) that can pose health risks. Such pesticide use was done in good faith by museums and collectors in the past to try to stop insect infestations. This mask showed no visual evidence of pesticide use. We are fortunate at the BMA to have a handheld Bruker X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer, which can detect heavy metals. The XRF readings at the various sampling locations supported the visual observation that no heavy metals are present.

A conservation treatment like this one involves more than just the objects conservator. Shannen Hill, former BMA Associate Curator of African Art, suggested that I take this treatment on, and Kevin Tervala encouraged me to finish it. Local objects conservators Angie Elliot, Diane Fullick, and Lara Kaplan gave me valuable input along the way. Cheryl Podsiki, an objects conservator known for her work with handheld XRF pesticide analysis of ethnographic objects, was also an incredible resource. Senior Photographer Mitro Hood and the BMA’s installation team helped show the mask to its best advantage, and the BMA’s conservation members were cheerleaders throughout the treatment. Many thanks to all!

Christine Downie