The artist’s work confronts our celebrity-obsessed culture, click-based empathy, and attention economy

A 2015 open letter to Amnesty International (AI) from Meryl Streep, Gloria Steinem, and more than 400 other prominent figures and organizations reads: “… your ‘Draft Policy on Sex Work’ is incomprehensibly proposing the wholesale decriminalization of the sex industry, which in effect legalizes pimping, brothel owning, and sex buying.”

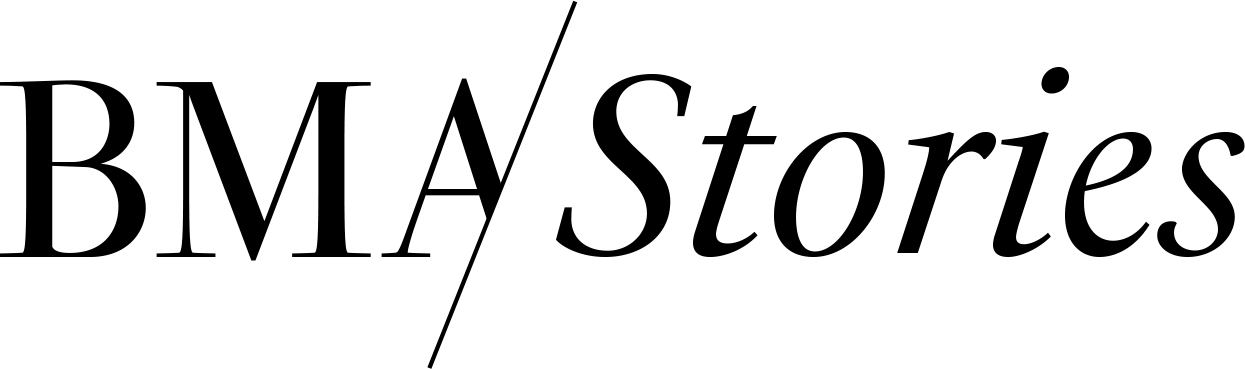

The subsequent public debate on the topic is the subject of Candice Breitz’s installation, TLDR. The work borrows its name from the acronym meaning “too long; didn’t read,” which is used by Internet readers as either a face-value commentary or a signal that they are making a quick summary of a longer, more complicated work.

AI recommended decriminalizing the purchase as well as the sale of sex work, seeking to prevent forced labor and human trafficking, abuse, violence, and the involvement of children. Sex work routinely forces sex workers to operate at the margins of society in dangerous environments, according to AI’s Policy on State Obligations to Respect, Protect and Fulfil the Human Rights of Sex Workers. It continues: “As a result, sex workers face an increased risk of violence and abuse, and such crimes against them often go unreported, under-investigated and/or unpunished, offering perpetrators impunity.”

This international dialogue hits home as well. A 2019 study on sex workers’ interactions with the Baltimore City Police Department published by Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health backed existing calls for decriminalizing sex work instituted in combination with additional strategies to increase sex workers’ health and safety.

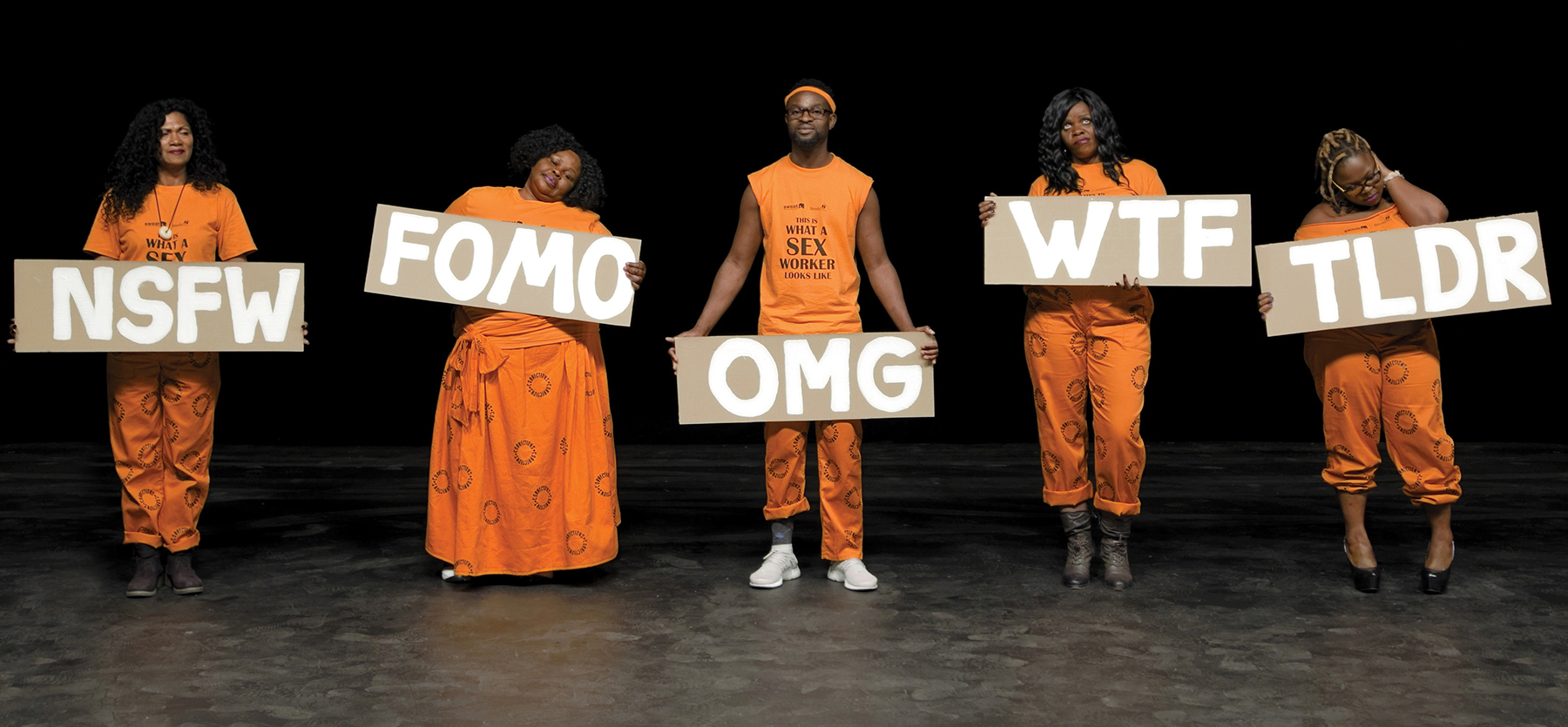

In an effort to be memorable and attention-grabbing, a 12-year-old boy addresses the camera in TLDR and on either side of him, screens show a modern-day Greek chorus of 11 South African sex workers holding protest signs. Later in the video, a soundtrack of pop songs transitions to protest songs, sung predominantly in Zulu and Xhosa. Interviews with the workers from the chorus provide context and further insight. Through this symphony of emojis, music, and theatrics, viewers learn the details of AI’s efforts.

The big question for an artist like myself—privileged, white, middle class—is how and whether one can be an ally without simply interfering from a perspective of entitlement …

TLDR is about what we pay attention to and why we often pay attention for the wrong reasons, Breitz (South African, b. 1972) has said. “The big question for an artist like myself—privileged, white, middle class—is how and whether one can be an ally … without simply interfering from a perspective of entitlement, like the Hollywood actresses in TLDR, self-appointed white saviors who swoop down to rescue ‘the poor prostitutes,’ without stopping to wonder whether ‘the poor prostitutes’ actually want or need to be rescued.”

SEEKING ASYLUM

Breitz first explored the questions “What do we pay attention to and why?” in Love Story. The 2016 multichannel video installation compels viewers to examine how we respond to real-world atrocities and the portrayals of those atrocities onscreen through two versions of six refugees’ stories.

The first version is 74 minutes of expertly produced excerpts from interviews with refugees performed by Alec Baldwin and Julianne Moore, each seated in front of a green screen. The second version is more than 22 hours of interviews with the subjects themselves. José Maria João is a former child soldier from Angola. Mamy Maloba Langa, a survivor of torture and abuse from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Shabeena Saveri, a transgender activist from India. Luis Nava, a political dissident from Venezuela. Farah Mohamed, a young atheist from Somalia. And Sarah Ezzat Mardini, a teenager who escaped war-torn Syria.

In her interview, Mardini talks about following smuggler routes for 25

When the motor failed and incoming water began to push the boat down, Mardini, a trained swimmer who had competed at the national level, jumped into the night sea. For three and a half hours she swam, dragging the boat and passengers to the Greek shore, aided by her sister and two boys.

“I was sitting there hearing a small baby cry and [thinking] I should do anything to help other people … I looked at the water, and I feel [sic] like it’s the first time in my life I jump into the water. I was afraid. But I thought it’s ok if I die for this

Candice Breitz: Too Long, Didn’t Read is curated by The Eddie C. and C. Sylvia Brown Chief Curator Asma Naeem.