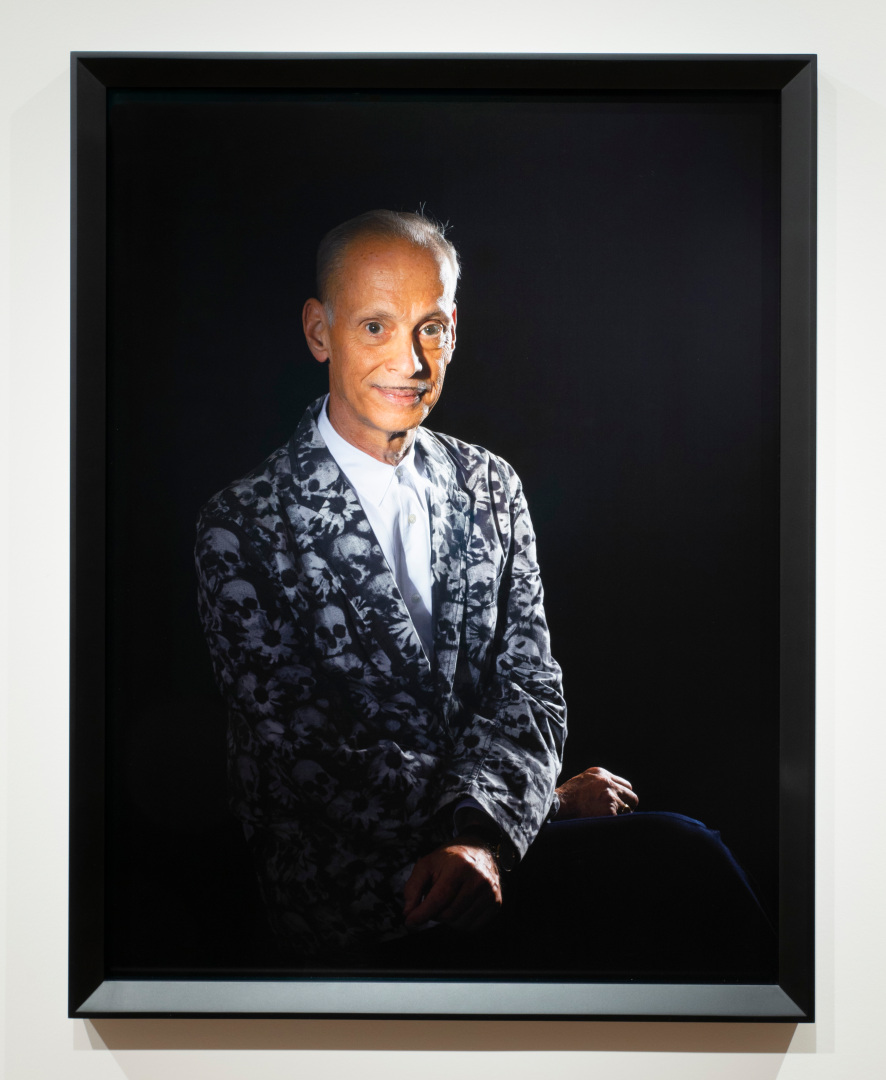

Photographer Catherine Opie and multimedia artist Jack Pierson spoke with filmmaker, producer, writer, artist, collector, and BMA Trustee John Waters in his Baltimore dining room in January 2022 to discuss the underlying themes of his art collection, featured in the BMA’s Coming Attractions: John Waters. Portions of their conversation are below with light edits for clarity.

Cathie Opie: Jack and I see certain themes running through the collection. I was wondering if you could name the themes that you see.

John Waters: Firstly, I always love art that infuriates people. Sometimes it infuriates me first, and it takes me a minute to realize I love it. And that’s when I know I’m going to buy it.

Secondly, I would say art that makes me laugh in some way. Because contemporary art is often witty, but is it ever funny? I think that’s a very, very delicate question. And “funny” is looked on with suspicion, but sometimes Mike Kelley’s pieces are so rude that they make me chuckle.

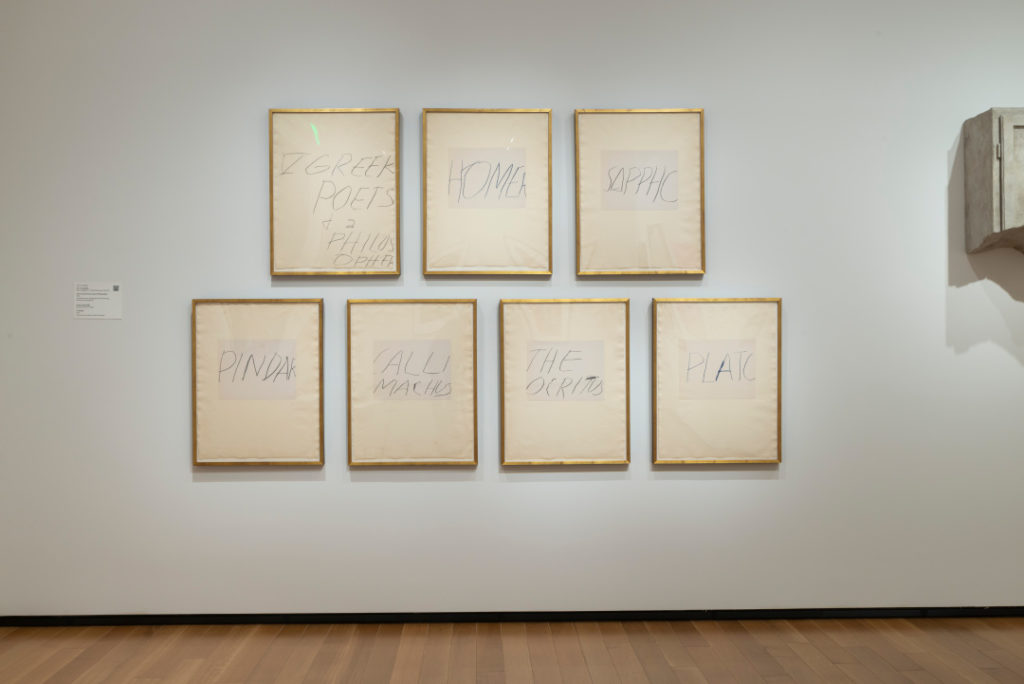

Confidence, that’s the third one. Perfect example—Cy Twombly. Imagine him showing his scribble drawings to people for the first time. He gave them to friends, and they threw them out. The confidence to believe that what you have done is perfectly valued even when no one else agrees. I don’t think the artist should ever call themselves an artist. I think that’s up to others. When people say to me that they are an artist, I always think silently: I’ll be the judge of that, history will be the judge of that, not you.

Fourth would be narrative—filmic in a way, even though it doesn’t have to be about movies. But narrative—imagined or otherwise—that tells a story that other people might not get. That goes along with confidence too, I think.

Catholicism—I guess there’s some leftover of that in my damaged psyche. Sexuality, yes, but in a way that’s always kind of creepy or funny but not just sexy. I’ve never jerked off to any artwork. Is that a question?

CO: I don’t think that that is a common question I’ve seen.

Jack Pierson: Maybe that’s the title of the exhibition.

CO: John Waters: I’ve never jerked off to any artwork.

JW: That I own! Those are my themes right off, I guess. Did you have any of the same themes?

JP: Part of what I see is kitchen-sink realism since we’re talking filmic. This occurs with the Richard Baker and Doug Padgett works.

JW: George Stoll, too. Working with your mother in the kitchen—

JP: Yes, exactly. There’s also a disaster element—

JW: I curated a whole show called Catastrophe at the Merola Gallery [in Provincetown, Massachusetts].

JP: All of them dovetail. The disaster goes in with your Christopher Wool photograph of his studio. It’s—

JW: Well, ugly! I think that’s the thing. Ugly.

JP: It’s a disaster, but it’s realism—ugly realism.

JW: Because it’s hard to do ugly, right? Everybody kind of tries to—

CO: Well see, I wouldn’t call it ugly. I always think of ugly as “bad art.”

JW: That’s a different thing. Do I own any works that I think are purposely bad paintings? I don’t know that I do. Christopher Wool’s photograph is the ugliest thing I own in my collection. And I look at it in awe that any artist could take a picture that ugly.

And that’s the problem with cell phones. Diane Arbus wouldn’t have been able to use [them]… They make every picture look beautiful, like a travel poster! You can’t take a bad picture. That’s the enemy of art.

JP: Okay, but what about Kathe Burkhart? That’s purposely bad.

JW: Well, okay, it’s purposely bad, but she’s also a film buff. Because she takes an Elizabeth Taylor movie every time and then writes words that a feminist would never write, usually “slit” and “cunt” and that kind of bait.

JP: This leads into the third theme I’m coming up with, which is kind of, “What the fuck?”

JW: Is that the same as pissing off people? Like Peter Fischli and David Weiss and those airplane pictures? Why is that photo so big? Why did anyone take this picture? It would be the third reject in a barber shop calendar. Now I never look out the window in an airport without thinking of that work.

I think the piece that sums up this outrageousness more than any of my collection is the Mike Kelley collage. That made even the sophisticates I know in the art world mad when they saw it.

JP: Right. But there’s a lot of that going on, like with this Cy Twombly suite of lithographs.

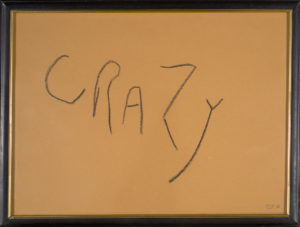

JW: It completely made my father insane when he saw that hung on my wall. He always used to gripe, “You bought that? They saw you coming, boy.” And the dealers did! But that’s how my dad and I could talk about contemporary art. He was just amazed and stupefied that anyone would want to own this piece. Look at that drawing he did —C-R-A-Z-Y—to show his contempt for my Twombly purchase. He was mocking it but somehow did get it right. He understood Twombly without ever realizing it.

I taught an art class at a grade school recently. And we had one class on Cy Twombly. The students never made fun of him. They loved the drawings. We turned out all the lights, they were blindfolded, and they drew like Cy Twombly. The teacher said, “I’ve never seen them act like this before.” Imagine when they went home with their scribble drawings and showed them to their parents. They’d say proudly, “Look what we did!” And the parents probably complained. But the children completely got it!

I think art’s job is to make you mad. To challenge you, and make you look at something in a different way. All the pieces I’m donating have spoken to me because I live with them, and I look at them every day. I wrote a chapter called “Roommates” in my book [Role Models], which is about the artists I like the best. They are my roommates, and I have a lot of them! I don’t own one piece I can’t hang up. I only buy little art now, because all my walls are full.

JP: I was wondering whether talent got in your way as a photographer or a collector?

JW: I think more as a photographer than a collector. I never knew all the rules of photography, I never developed one of my photographs ever. But as an artist, Andy [Warhol] could draw way better than what he’s famous for. And to draw those soup cans? It’s not easy! To paint those soup cans is hard if you think about it. Talent isn’t enough. A million people can really paint. But how they paint it and what they paint, and what you do with it, those turn it into the magic trick of art, to me.

CO: One of the films that I always show in all my photography classes is Pecker. Because it’s about photography in a different way.

JW: Well, it’s about the art world, but he’s more of an outsider.

CO: Yeah, exactly. He’s an outsider artist that gets discovered. But I’m just thinking about that and your own relationship to photography in your collection and as a filmmaker.

JW: People thought that I was either Pecker or Cecil B. Demented. But I’m not either. Cecil B. Demented was a cult leader but he had absolutely no sense of humor about himself and hopefully I do. And I’m the opposite of Pecker. I knew about the New York art world, and I wanted them to come down and discover me. Pecker didn’t. I wasn’t naive, that’s the difference.

I’m for the elitism of the art world. I think that art for the people is a terrible idea. To me, art is like a biker gang. There are extremes: you have to learn a special language, there’s a killing room. It’s all hilarious. And you must dress a certain way. When the art world went to Marfa, Texas, the locals thought Satanists were moving in because everybody dressed in black.

JP: The final theme that I was seeing is the notion of touchstones and people that make a difference to you.

JW: The person that taught me the most about art was Brenda Richardson [former deputy director and curator at the BMA]. She really taught me everything [about collecting art]. She gave me my first film exhibition in a museum at the BMA in 1985, too. That was before Hairspray, so people were outraged that the government would pay for my so-called disreputable movies to be shown. Brenda encouraged me when I started taking my photos. She was my very first collector.

CO: Is there anything that you’d like to add about the work going to Baltimore, and Jack and I curating it?

JW: All three of us have a common history in some ways, and a common taste. And even though we might not agree on some pieces of art, we all have a sense of humor and that’s how we get through life. That’s how we change other people’s minds. Make them laugh to listen.

Generous support for this exhibition is provided by Clair Zamoiski Segal and the Clair Zamoiski Segal and Thomas H. Segal Contemporary Art Endowment Fund.