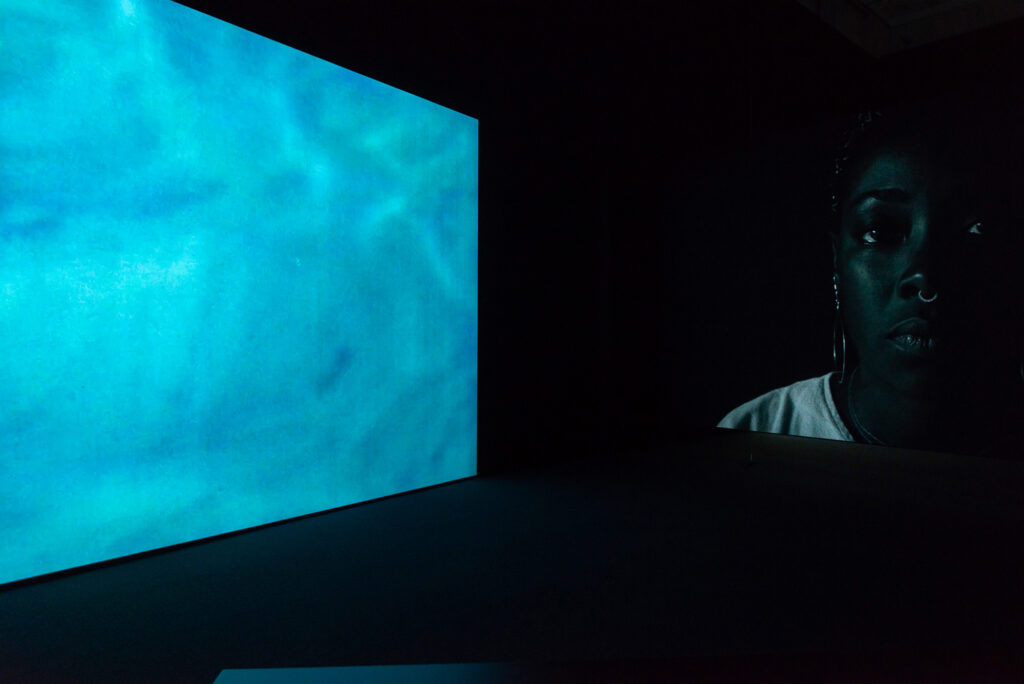

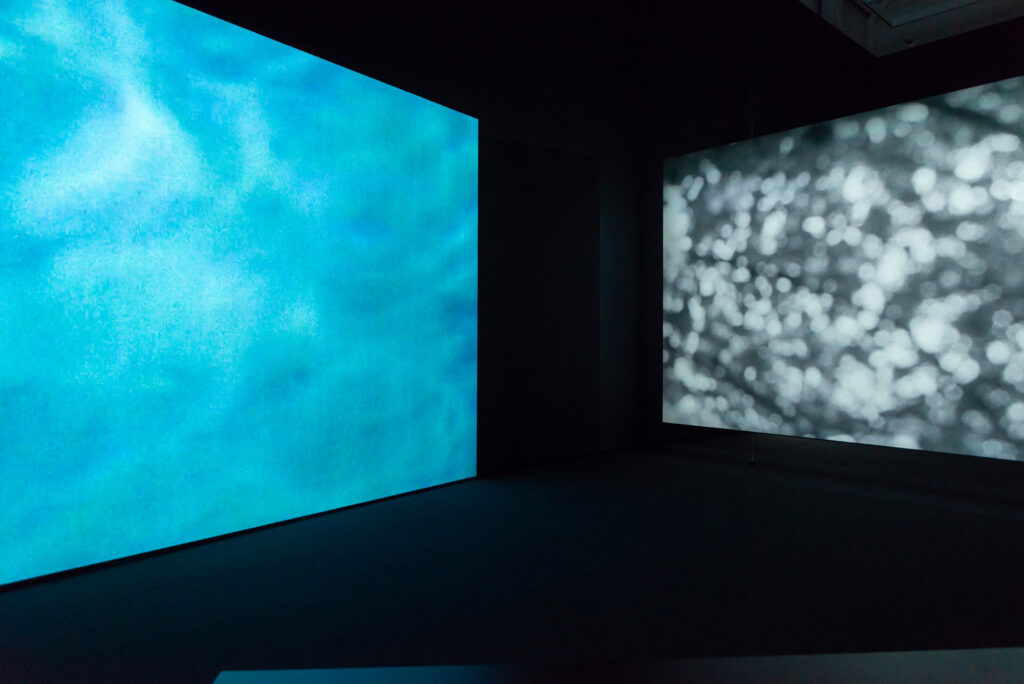

Elissa Blount Moorhead and Bradford Young’s Back and Song considers the labor and care provided by generations of black healers, including their historic contributions to and resistance of Western medicine’s flawed and discriminatory structures. The Baltimore-based artists’ four-channel video installation was on view through January 3, 2021, in the Contemporary Wing of The Baltimore Museum of Art. The exhibition was presented as a part of the BMA’s 2020 Vision initiative, a year of exhibitions and programs dedicated to the presentation of the achievements of female-identifying artists.

In February 2020, Blount Moorhead and Young connected with their friend, frequent collaborator, filmmaker, and cinematographer Arthur Jafa to speak in-depth about Back and Song via video chat for the first time together. A lightly edited transcript of their conversation was published as a three-part series on BMA Stories and as a PDF.

Part 3 of 3

AJ: Well, give me a very schematic breakdown of the process by which you guys arrived at whatever the initial ideas were. And then how you developed them and how it came together. How it was actually implemented. And maybe in that part talk a little about your working relationship with Stefani [Saintonge] more specifically.

BY: We basically started with some key phrases, words like jazz, Haile Selassie, we just went down the whole line of things we thought were things to pull from. Herbs, midwifery, we just went down the whole line. It was I think about 15 key words that we decided we would hand off to our archivist collaborators Rianna Jade Parker, Huddah Khaireh, and Elijah Maja. To have them pull based on that.

AJ: Wow, interesting.

EBM: They were calling them prompts, but they were mad esoteric. They weren’t like how people normally think of search prompts or finding aides. It was not that.

AJ: Well, I mean it’s funny. When you mention it, what comes to mind for me more than prompts, obviously I’m just saying prompts, but more like mantras. Words that, when you say those things out loud, they resonate and structure things. In very not necessarily linear ways.

EBM: Absolutely.

BY: Yeah. Yeah definitely. And then they came back with their first iteration of that, and it was funny. The first riff on it was not… they had some stuff, they had some connections. And then we told them to expand on it and they went back and came back with another version. Another folder, if you will, of more options and then that’s when it really started to unfold.

EBM: There was more conversation at that second iteration because that started—instead of that becoming where someone briefs you and then they deliver—it became the beginning of a good conversation. So, one image would prompt this and then there would be a discussion about a book. Things that didn’t necessarily show up as concrete responses but were about circular discussions to confirm that we all cared about the same kinds of inquiries basically. Not even the same stuff. Just the same questions.

BY: Right. Yeah and once we got an extensive vault of things, we then brought Stefani in. She was always in the conversation, but at that point we really brought her into the conversation in the sense that she had the same mantras, the same prompts, she had access to the footage. And we gave her a schematic layout of how the installation, in the sense of it spatially, how the screens were going to be orientated. And what that story was about. We had, if I can remember, the left screen was Euphoria, and the right screen was Rest. And then the center screen we knew were going to be healers.

EBM: In the loosest sense as well. Not just people who worked in health directly but one of the healers is a woman who runs a funeral parlor and does the makeup in particular to prepare people. So it’s not just medical or whatever.

BY: Film makers…And then she went, and she started cutting. She looked at the footage, went through the archive and started cutting the stuff together based on that story. The story of the screens. And we were well on our way then. And that’s the thing about Stef, is that it doesn’t take much for her to get there.

We actually had to go back. What’s funny is that we thought we didn’t have enough, but then we realized that we had a link that had an insane amount of footage. So at first we were like, man there’s not a lot here. And then we were able to open a link that had literally an Excel spreadsheet of descriptions and, yeah, the actual spot where we could rip it from. And funny enough, we sent that to Stef, because she would dig in without the prompt of how you could activate it, and she sent us back something that was good but we felt it was missing a bunch of really important pieces. But once we told her hey, click on that link, she went back and clicked on a link and I remember her response was, “Oh okay. I didn’t realize that had that much material,” and she went back and began to…and then that’s when it just started coming alive. And honestly there wasn’t much, after her first cut or two, we were pretty much well on our way.

EBM: Yeah and watching her footage, as well, at first it was just me and you watching them separately and responding, like, “Oh shit, did you see that? Oh shit, did you see that?” And then a couple times together and you see something and you’re running around the room, you know how it is. But also she was simultaneously looking at things and having similar responses, but also having her own views about things, so things would come back to us and we’d be like, “Whoa yeah. Okay, she’s way ahead.”

BY: Yeah. And then we were cutting all the way into the 11th hour, of course, as we always do. And then we felt there was a need for us to… Stefani actually did the initial sound design for it. And most of the sound is obviously mostly from the actual archival material. At that point, all of it was actually from the archival material. So she was stretching and cutting and expanding and overlapping and doing really interesting things that we knew had to be mixed out later and sweetened and focused. And then it was at that point that we realized we just needed another layer on top. And that’s when we approached Esperanza [Spalding]. And she basically got the final version of the four-channel piece itself and she was able to…

EBM: I think Stefani gave it to her, gave her Euphoria and Rest side by side. And I think, from what I remember, because there were also things that we were doing with the sound with Stefani, like dropping out the authoritative narrative of the anthropological stuff. Which I think is maybe my favorite part, is taking out the part where ostensibly they’re doing some sort of training. That infamous midwifery video where these white medical doctors are gonna come tell us how to be clean and all that sort of stuff. And obviously, we’re doing something where we’re juxtaposing it with our existing cleaning rituals. But that potent silence, which is not associated with birth when it’s medicalized versus when it’s in its natural state with a person you trust. So, dropping out his commentary and making it more absurd by not having it there. So those happening in the sound already and then when Esperanza got it, she was looking at those two things together with the single soundtrack over both of them and the way that they were inter-playing with each other. And then she was in.

BY: Yeah, then she was in. And that was pretty much the process. It took time obviously because I think-

AJ: How much time?

BY: Oh man, six months?

AJ: Six months? Wow. Okay.

EBM: That was May at first, or April, Brad?, and then the show was in October so whatever that is.

AJ: And Stefani, she was working remotely. So where was she based? I’m just trying to get a sense of how you guys…

AJ: Oh, she was in New York.

BY: Yeah she was in New York.

AJ: Okay, that’s not so far actually.

BY: Yeah.

AJ: I thought y’all were going to tell me she was in Haiti or somewhere.

BY: Nah, nah, nah.

EBM: She almost was.

BY: Yeah. I was in LA. Elissa was in Baltimore. She was in New York and our archivists were in London.

AJ: Oh okay.

EBM: Yeah.

AJ: That’s a pretty, widely spread out. You know what I mean?

EBM: Yeah.

BY: Yeah totally.

AJ: I think those kinds of things really do affect the projects involved, you know, where people actually are doing various kinds of work on them, increasingly. I think about that. Some if it is just like your personal intimate space that you work in, but also some of us, like you said Elissa with the ley lines, some of it really does have to do geographical energy or something like that. When I look back at where I’ve actually been productive, or more productive, rather than less productive.

EBM: Are you more productive in LA you think?

AJ: No, I don’t edit in LA so much. I do a lot of thinking here but most of my things…

EBM: In New York.

AJ: …strangely enough, yeah New York. The White Album was Berkeley, you know, I mean, Berkeley, then Berlin. In a strange kind of way, it’s more like I’m gathering stuff here or something, or coalescing stuff. But I just wonder about that with other people. Like, Daughters [Daughters of the Dust] was edited in Atlanta, say for example. You know what I mean? Something real specific about where you are when you assemble things.

BY: That’s healing. That’s healing, man.

EBM: And maybe, yeah that’s interesting. Because when people were together, we were so happy. When we were together in Baltimore we were obviously happy because we could be close to our kids and stuff, and to each other, but we were really happy to be together and, I don’t know, I feel like that’s reflected especially in the portraits. All of those are in Brad’s kitchen slash living room. Except two, which I shot in Philadelphia and nearly botched, not knowing what I was doing. Brad crazily trusted me.

BY: And then the colors were shot by us, partially by us, and partially by Olu and Ayo [Young’s sons]. They shot. Which is also great. The colors, the color blocks.

EBM: The light, that was light that was new because Brad was just moving into his house and so all those things that were shot were shot in the biggest opening of light in his house, which is interesting. And the boys were around while it was being shot and Idahn [Young’s daughter] was trying to be born.

BY: She was born the day after. No, no, no she was born two weeks/three weeks after the opening.

EBM: No! Because it was…

BY: No, no, what am I talking about. She was born ten days before the opening.

EBM: Yep. Couple days, because you remember you had to go back, because we were driving back and forth to Philly to install. That’s a whole other element of it, AJ. The initial space was wild. We looked at about five or six spaces on the phone while Brad was in London. And me and Brad went back and forth to Philly, which is only an hour from Baltimore. But that was good too, riding back and forth, back and forth, between here and Philly. Because Philly has another kind of interesting second city energy. But it’s not quite like Baltimore’s Blackness thing. It’s very thick here.

AJ: I have another question. It’s kind of related to what I just asked about process. It’s something I think about increasingly. Because I think it’s also bound up with the whole well-being thing. It’s like—practices. Or not just practices, but best practices. Having come out of the process, if somebody asks you, “Well, what are the two, perhaps three, things that you feel get added to an ongoing accumulation or compilation of best practices?” In particular, things that are not orthodox, or maybe seemingly non-causal. Or things that just would be typical. What might come to mind is—oh yeah, that’s something that we’ll be seriously adding to or under serious consideration for a best practice. In terms of the actual composition and making of the film and all this kind of stuff.

Because, just to say before you answer, the whole idea of having mantra prompts as a start—It’s not the start because you’ve got to have a vague idea in your head, but the first time it gets turned into concrete things—And then using those as triggers for other people who are going to be participating in the process. That sounds like a very, very, very interesting, atypical way to structure a project. I think. But I’m just wondering in general if you guys have any sense of best practices.

EBM: Okay, I want to say something, because Brad will be shy. Because I think he has some very serious mastery around the project of collaboration that I admire. We’ve talked about this, AJ, how the collective idea makes us all recoil because thinking about making something by committee, and maybe you all have particular scars because you’re cinematographers, making by committee is filmmaking. But I have other scars around making by committee. So collaboration is something that, often, us free people are afraid of or we’re just whatever.

But Malik [Sayeed] said to me something once to the effect of: make sure you always work on things that you know—I’m going to get it wrong…not low stakes, but that all of your neurosis and high stakes stuff is not attached to in a way. That you give yourself a chance to work on things that basically you can play around with. And, AJ, we’ve talked before about that where you’re saying musicians go and play together. Where in other things like film, for example, it feels more like work. And so I think Brad had some very serious mastery or gnosis around entering this as a project where, “I get to play.” And I joke all the time and say—I just want to do hoodrat shit with my friends—but that’s true, right?

This was also about being together, being in a city that we think we’re choosing, and being not stressed about it. So there would be outcomes like (I was saying at one point when I botched the film or whatever) that required both of us to let go. So yeah. I think that was a big thing—that letting go—in the way that I found that to be, for me anyway, I think as a person who’s also been to design school and finished design school, where it’s more of that assembly line versus the passing the basketball analogy, AJ, it is really a miracle and a blessing. As Brad says.

Because you can be really precious about certain parts of your making and it has to do with things you tried to push out of your body all your life. It has to do with access, or your ability to make things or not make things based on money and all kinds of things. And this was kind of free of that. And that was a decision. I’m saying that because Brad doesn’t always admit or acknowledge how much his generosity is a praxis, and a particular way of being in the world. What he lets go of, what he holds on to, allows for a creative process that is, I don’t know, I think it’s miraculous and very satisfying.

AJ: Well, let me ask Brad something real specific then, given what you just said. Do you think this is global for you, Brad, or how do you think that works in relationship to the work you do with Elissa or maybe some other things, versus you doing a job. Big budget, big budget, or whatever.

BY: Right. Right. Well, I think it goes back to the whole pedagogy. My understanding is that the way we’re executing the work, let’s say for instance when I’m with Elissa or I’m with Leslie [Hewitt]. Or whoever. Artists in the quote unquote “art space,” but specifically on this occasion with Elissa, is that this is the way it’s supposed to work. This is the way it works. This is how it is when it works. And this is the way it’s supposed to work. And that’s very loose and up for debate when I’m working in big budget films. It’s not easy to run across kindred spirits who have the same security, lack of insecurity, around how to make films.

Everybody says it, filmmakers are always saying: “Oh, it’s such a collaborative process.” But when you got to put your feet on the ground and start collaborating, it seems that people pivot from that and it’s hard. It’s not always easy. You accommodate, and you make logical compromises, and sometimes you learn a lot when the process is not so collaborative and sometimes it renders bad frames. The process itself gets in the way of the actual making of images.

So all I’m trying to do when I’m doing these projects is try to live by example. Create by example. Just remind myself that there is a way that works for me as an individual collaborating with another individual, but there is also a way of working that cosmically works. And I feel like this is the divine order of things. We’re supposed to hold hands. This is what the creator intended us to do, is to make things together. So for me it’s easy.

EBM: And Brad again, I’m being dogged about marking it because of what AJ said earlier about focusing on practices. As a practice, right? Some of these things, as a framework. And, AJ, we’ve talked about it before and as a woman making work with men often, it’s important for me to identify all the time. And we’ve talked about it in terms of space I watched you support for Tourmaline on the Marsha P. Johnson set, or when we made 4:44, or all sorts of ways this shows up with you. And then with Brad, it is something that I think is global in a particular set of circumstances and it’s very anti-patriarchy. I know it, I recognize it. And I didn’t expect to find that in collaborations with men necessarily. Of course I find it in many collaborations with many women. But it is more pronounced than with some people.

It’s also very consistent. When we did the Common, Black America Again, it was a similar thing. Brad built a set around a fellowship, around food and breaking bread. Who does that? And with Kamasi [Washington, for the 2018 film project As Told To G/D Thyself], the same way. Breaking hierarchy in a way that I know is not native to a film environment where not just Brad but, also Jenn [Nkiru], and Terence [Nance] subvert hierarchy. I’m not a casting director, but I casted by gathering and bringing together local energies to deepen the narrative. And I was made to feel like I was an auteur in that space, and that we were just trying to create something in a way that re-creates an experience we keep feeling over and over when we watch it together. So a couple projects in now, I recognize it as a practice, whether it’s conscious or unconscious. It should be marked and thought about more as an ethos.

AJ: Well, I got a last question. And it really is a throwback to things that you brought up earlier. But I just want to re-pose it. It’s this whole thing, the relationship between play and well-being.

BY: Yeah. Yeah. Making stuff is playing really. And playing is fun. I don’t even think I have the language to remind us how important it is for us to play—have fun—while we make. And how healing that is. How cathartic that is because you get to do something that’s so innate to our humanity. Which is play.

EBM: And you know, it’s real. I look in the reflection of it in my kids when I’m with you, both of you, they don’t think I’m working.

BY: Exactly. Yeah.

EBM: In LA, before, they were so happy and everybody felt like ‘oh we’re getting to go visit family and be with people’ and even when you’re in a literal workspace, like an edit room, Sunny [Moorhead’s daughter] is like, “Oh we get to be together.” And the same thing here. It wasn’t not arduous, I guess, making Back and Song. It was a long time and if I had been doing anything else that I have to do for 6 months, it shows up. And Ziggy [Moorhead’s son] is always like, “Mommy, are you sleeping? Are you okay? Are you tired? You’re working a lot” when I’m doing some things. But with Back, I think they just showed up at the show and they were like, “Oh, this is it. You guys were doing something.”

BY: Right. Right. Exactly, exactly.

EBM: It’s like a real reflection. And I was thinking last night, AJ, when you asked something and I was trying to put it in a… like for example, I was thinking about how so many of the things that you make—and that TNEG aspires to make, particularly Love Is The Message—it’s that associative thing. It’s something about associating images but also that passing the ball thing that keeps coming up. This emanation. And then I was looking at BLKNWS and it reduced me to tears over and over because it was so good. And it was because it was more like reportage, right? It was different than the way that you constructed things, but it was still resonating in the same way, right? And I was just reading Saidiya’s book [Saidiya Hartman] about also taking archives, even though it was in a printed page, but hers is more about extrapolation, and into the imaginary. Right? But it’s still all the same thing, and so I was like well, where do we fit in in that? Like what were we doing? In retrospect, I think it was something more aligned with ritual and performance.

BY: Right. Yep. Yeah.

EBM: And that’s what I like, that’s what I love. It makes sense that it would be more of a performance, but not in the sense of performance of other people. It was something about bringing people in. To a ritual or a gathering or a fellowship or performance or something. So that feels to me, that’s like play. I would love for every Sunday to be that.

AJ: Right. I just kept thinking, I think it’s Godard [Jean-Luc Godard] who was saying the difference between making a political film and making a film politically. In relation to this whole question of play, but not even just play, but the well-being part of it mostly, is to what degree if you’re making a film… I guess it’s three parts of it: 1) a film about well-being in the Black community, 2) a film that affects well-being or has the capacity or the desire to affect well-being in the Black community, and 3) a film that was made well, or made in a way that it reinforce well-being. You know what I’m saying? Those are three separate things that have some sort of relationship to each other, I think.

EBM: I love that, yeah.

BY: Oh I think yeah. Yeah.

EBM: It doesn’t matter what it looks like. I don’t think it matters that it’s a film with midwifery and healing. It could be a horror movie. It could be Ericka [Blount Danois, Blount Moorhead’s sister] and I working on a comedy together. It’s fun. It feels like play all the time, even if we’re fighting about something. I feel like I’m back in my childhood bedroom, steeped in our political and cultural surroundings just making up stories. So I don’t think the content itself has to be overtly political. It is the making of the film politically that bleeds through. I love that quote. Because really, it’s the approach. It’s the emphasis on the approach and what brought us to this point of view.

AJ: Okay do you guys have any final thing, I think, that you want to say just in general?

EBM: No.

AJ: But do you think we have enough? I think that’s enough right? Because…

BY: Oh yeah. Oh yeah.

EBM: It’s everything. It’s all all the things in there.

AJ: Okay. Okay cool. Travel Safe.

BY and EBM: Love you.

AJ: Love you guys.

Elissa Blount Moorhead and Bradford Young: Back and Song was on view at the BMA, as a part of the Museum’s 2020 Vision initiative.