Bill Gaskins’ poignant reflection on Valerie Maynard’s six-decade career first appeared in the 2020 exhibition catalog, Lost and Found, published by the BMA on the occasion of the artist’s retrospective at the Museum. Maynard, an inimitable artist and mentor who called Baltimore home for the past twenty years passed away on September 19, 2022.

This exhibition of Valerie Maynard’s work presents what amounts to, on the one hand, a small sample of her more than 60 years of commitment to developing and challenging herself and the audience as an artist. At the same time, the works selected for this exhibition also represent a vibrant network of community-based cultural and educational institutions in Harlem and New York City. These sites were essential components of a beloved community that guided, nurtured, and supported Maynard.

Essential sites for her development were the storied leadership academy, summer camp, and neighborhood center Camp Minisink; the Schomburg Center and Countee Cullen branches of the New York Public Library; the social and spiritual agenda of the Abyssinian, St. Charles, and Mother Zion Churches; a Saturday studio school scholarship at The Museum of Modern Art; the art scene of Greenwich Village; and the Studio Museum. Early on, art was something one did rather than learn, and what one did through art had nothing to do with making money from it. Drawing functioned as a fundamental, foundational vocabulary for expression and communication for a person who preferred listening and watching to speaking.

The skills and visual literacy of Valerie Maynard reflect years of profound independent study in drawing, painting, and sculpture and her mastery of these media. Aside from influences from Chinese and African art, her work is also evidence of a personal commitment to critically observe, with depth and engagement, the world and the times in which she has lived. These works also reflect the impact of a nuclear family that includes a brother, sister, and five uncles—a village of extended family, friends, and community. Moreover, understanding Maynard’s cultural and ancestral stream of consciousness as an American of African and Caribbean descent born to a world especially hostile to women and dark-skinned people is essential to comprehending her work.

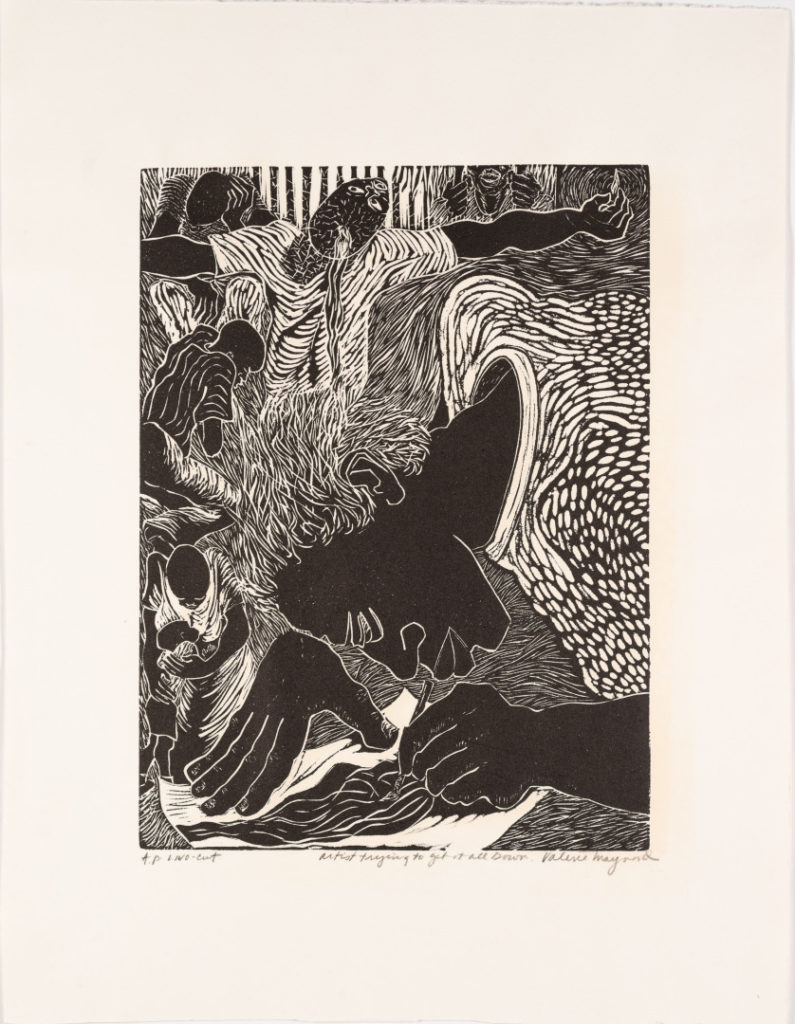

However, despite the historical, political, racial, and gender-specific forces in the life of the artist, Maynard’s work excludes no one who has ever been in love (or wanted to be), sought justice, or recognized injustice. Her work excludes no one who ever shared a moment with a parent, grandparent, or guardian, sibling or child, or God. Look at the hands of the people in Artist Trying to Get It All Down and see that they are large, open, and expressive, like the heart, mind, and hands of the artist herself.

Look at the hands of the people in Artist Trying to Get It All Down and see that they are large, open, and expressive, like the heart, mind, and hands of the artist herself.

In doing so many different things and doing them all so well, Maynard challenges the Western model of the artist as a socially isolated genius, restricted to a single medium of expression. Her participation in over 90 national and international exhibitions and her various teaching positions, fellowships, and residencies all signify the importance and legacy of Maynard among a handful of enlightened individuals and institutions. You are witness to so much more than an exhibition of drawing, painting, printmaking, and sculpture based on an interest in the traditional art historical topics of the figure, landscape, still life, the nude, and mixed media. Maynard is serving us news and the abstract truth. Her work defies categorization while being conceptually, culturally, and visually articulate.

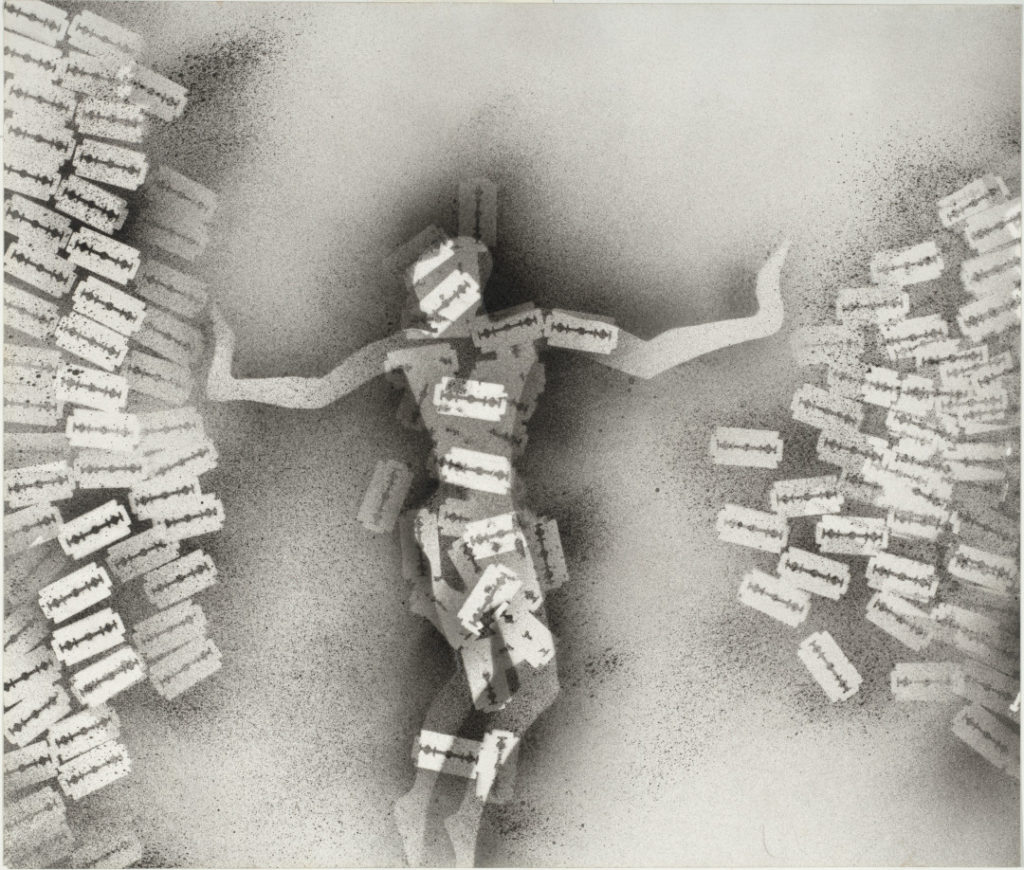

Aside from a pure exploration of materials, aesthetics, and conceptual possibilities, Maynard’s work offers a life-affirming joy that reminds us of who we can be as a human species. But Maynard also re-presents past and present acts of the human species at our ethical lowest through an aesthetic that seductively layers form, color, and symbolism as vehicles for ideas, scholarship, and nuanced personal observations. She exposes the suffering of people through structural inequalities based on belief systems that maintain their poverty and reduce them to landless, homeless populations, drifting across the earth by the millions.

Examples of this content are works like We Are Tied To the Very Beginning, the No Apartheid series, and the most recent series on the Statue of Liberty based on its actual and little-known history as a monument to the abolition of slavery in the United States. Through this work, Maynard calls upon us to embrace the power of love for social change and question the imagined power of social media likes as a stand-in for an actual human presence in our lives. Hers is the love James Baldwin wrote about in his book The Fire Next Time as a love that “takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within”.1 Maynard presents a collective and individual mirror before us as viewers. Through her work, we are all revealed as part of either the problem or the solution.

To fully appreciate these works, approach them as you should approach any human being—with a large heart, an open hand, and an open mind. There is so much to learn, experience, and feel. Consider the following questions as you experience and engage with this exhibition. What aspects of myself have I seen and know more about through this work? What do I know about the present through this work? What do I know about the past that I did not know before? What unexpected phenomena and concepts have I been brought to think about and consider through this work? What have I been moved to act on through this work? What am I afraid of facing within myself and the worlds beyond me? How much more grace and gratitude do I have through experiencing this work? Whom did I meet and speak with in front of this work? What did we talk about, and what did I learn?

The term “social practice” in contemporary art is a recent expression that emphasizes the artist’s engagement with communities beyond the commercial aspects and the white cubes of the art market. Maynard has been engaging others as a resident and citizen of those communities for most of her life. In fact, Maynard is not making “art” in the conventional sense of the term. She has been engaged in a labor of love for our sake rather than art’s sake, to again quote Baldwin “in the tough and universal sense of quest and daring and growth.”2

Externally driven ambition, awards, and approval have not been Maynard’s motives for working. The value of her production is not the result of appraisals from markets or museums, but the work itself and the essence of the person producing it. Maynard has focused more on knowing what she does (and why) than on being recognized for it. Consequently, beyond her beloved community, Maynard’s work and name are often absent from most accounts of postwar American art, and also from many exhibitions about the stories of black women and black artists transformed through the mid-20th-century civil rights, black arts, and women’s movements in the United States.

While she is relatively invisible to most in the art historical record compared to her contemporaries, Maynard is like other invisible and essential phenomena—like electricity.

There are two kinds of physics in the world: Newtonian and quantum. Newtonian physics studies physical forces we can see, like gravity causing an apple to fall from the interconnected branches of the tree supporting it. But there are invisible changes taking place long before the apple falls from the tree. These changes are the result of quantum physics, the small, invisible changes that are part of all progress in the world. While she is relatively invisible to most in the art historical record compared to her contemporaries, Maynard is like other invisible and essential phenomena—like electricity. While you may not see either of them at work, both exist as fundamental facts of our lives, bringing power and transforming darkness into light. The quantum and Newtonian physics of Maynard have impacted many, even those who have never seen or experienced the drawings, prints, and sculptures shown in this exhibition.

What these people have directly observed, experienced, and felt is a humanist practice that listens, guides, counsels, cooks, touches, engages, and gives the gift of time and undivided attention to those beings subject to inhuman treatment and disregard—because she is living among them but with an eye, ear, and heart beyond herself. Such values, some may say, can be at odds with the agenda of the contemporary art world. The work in this catalog and the exhibition are an extension of Maynard’s profoundly social practice. She has been an eternal flame of hope throughout her time on Earth. I am sincerely grateful for her extraordinary commitment to reminding us of who we can be as well as who we need to be as human beings in the presence of other human beings—in and out of her studio.

Notes

1 Baldwin, James. The Fire Next Time. New York: Dial Press, 1963, 128.

2 ibid