In 1792, Shinah Solomon Etting (1744-1822), a Jewish widow, sat for her portrait in Baltimore. Her portraitist, Charles Peale Polk (1767-1822), was a member of the Peale family, and many of his relatives—including his uncle Charles Willson Peale—were professional artists. Polk’s portrait of Shinah Etting (fig. 1), which is currently on view in Jacob and Hilda K. Blaustein Gallery of the Dorothy McIlvain Scott American Wing at the BMA, illuminates the complexities and contradictions of Jewish identity in America during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Through its composition and imagery, it suggests the prosperity and civic prominence of its sitter; however, this portrait also obscures the legal and social discrimination that Jewish Marylanders faced. Despite these challenges, the Etting family benefitted from racial hierarchies and the institution of slavery.

Shinah Solomon Etting was the matriarch of the Etting family. Her parents, Joseph and Bilah Solomon, immigrated to colonial America from London in 1742. They settled in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where Shinah was born. She married German-born Elijah Etting (1724-1778) of York, Pennsylvania, who was twenty years her senior. They had eight children together, seven of whom survived to adulthood.[1] In 1780, two years after Elijah’s death, Shinah relocated to Baltimore with her children. As a widow, she earned a living by operating a boarding house, which she maintained for more than thirty years.[2]

Shinah Solomon Etting clearly became a respected resident of the city, as Polk painted her twice. The second portrait is now in the collection of the Maryland Center for History and Culture (fig. 2).

A contemporary in her community in York, Alexander Graydon, described Shinah as the “sprightly and engaging Mrs. E., the life of all the gaiety that could be mustered in the village; always in spirits, full of frolic and glee, and possessing the talent of singing agreeably, she was an indispensable ingredient in the little parties of pleasure which sometimes took place.”[3] Indeed, in the 1792 portrait, Polk conveys Etting’s congenial disposition by showing her smiling. Her expression is friendly and inviting, and she appears ready to engage in conversation.

Polk’s portrait of Etting emphasizes the elegance of its fashionable subject. The artist presents a lavish symphony of colors, patterns, and materials, from Etting’s gauzy, voluminous bonnet to the crisp folds of the fan in her right hand. Elements of this painting echo other portraits that Polk produced during the early 1790s (figs. 3 and 4). His portrait of Mrs. William Clemm (née Catherina Von Schultz), c. 1790-95, for example, features a similarly elaborate bonnet and, like Mrs. Etting, Mrs. Clemm holds a sprig of greenery. Polk’s portrait of Emily Smiley Snowden, 1793, in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum features an almost identical shawl and fan to those in the portrait of Mrs. Etting, suggesting that perhaps these were props that the artist kept in his studio.

Through these visual similarities, Mrs. Etting’s portrait communicates that she is equal to her fellow citizens. This painting does not call attention to the Jewish identity (and thus cultural difference) of its sitter. She is visually indistinct from other white women who had the financial means to commission painted portraits. However, Jewish Marylanders were extremely few in number. According to an estimate by Shinah’s son Solomon Etting (1764-1847), there were only 150 Jewish people in Maryland by 1825.[4] In comparison, the 1820 census recorded the total overall population of Maryland as 407,350, including 62,738 people in the city of Baltimore.[5] Jewish citizens of Maryland also faced legal discrimination. Anyone who wanted to hold public office at the state level had to express their adherence to Christianity. A businessman and banker, Solomon Etting contributed to the campaign to remove this requirement. As early as 1797, he petitioned the state’s House of Delegates to grant Jewish people the right to practice law and hold public office.[6] Following years of debate, in 1826, a bill granting these rights passed, and Etting became a member of Baltimore’s City Council shortly thereafter.

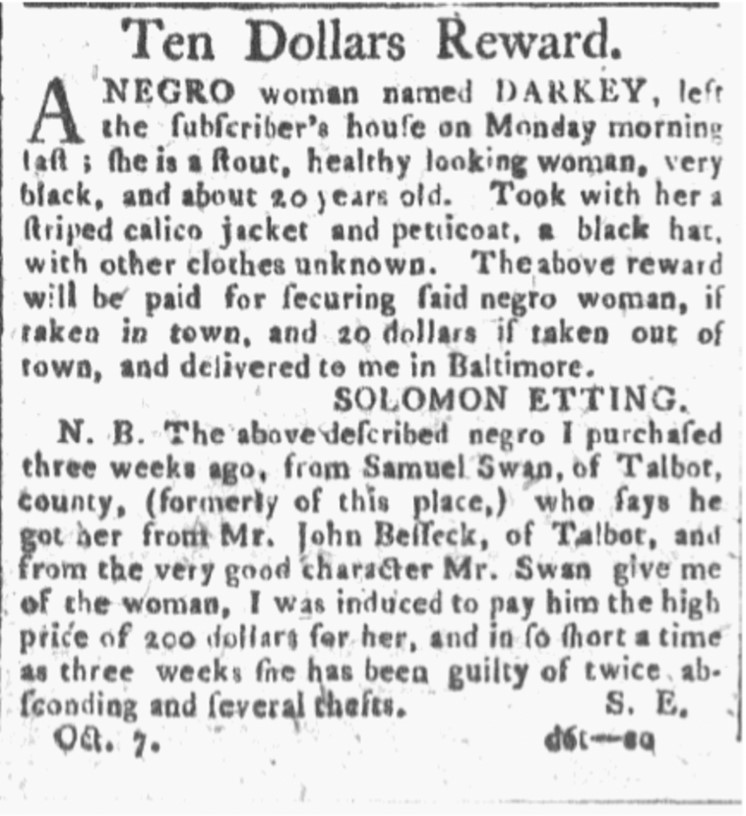

Despite his many accomplishments, Solomon Etting’s legacy is complex. Although he lobbied for Jewish civil rights, he was himself an enslaver. While living in Lancaster in 1788, he enslaved a woman named Dinah, along with her two young children, Margaret and Henry.[7] Following his relocation to Baltimore the following decade, he published a notice in the city’s Federal Gazette seeking a reward for an enslaved woman who had self-emancipated (fig. 5).[8] Ironically, although he fought for the rights of one minority group, he actively participated in the ongoing disenfranchisement and abuse of another. In later life, Etting held leadership positions in Maryland’s branch of the American Colonization Society, an ostensibly benevolent organization that advocated for sending free African Americans to Liberia. However, this organization used the press to stoke anxiety regarding the growth of the state’s Black population.[9] This constellation of actions suggest that Solomon Etting’s personal beliefs were replete with contradictions.

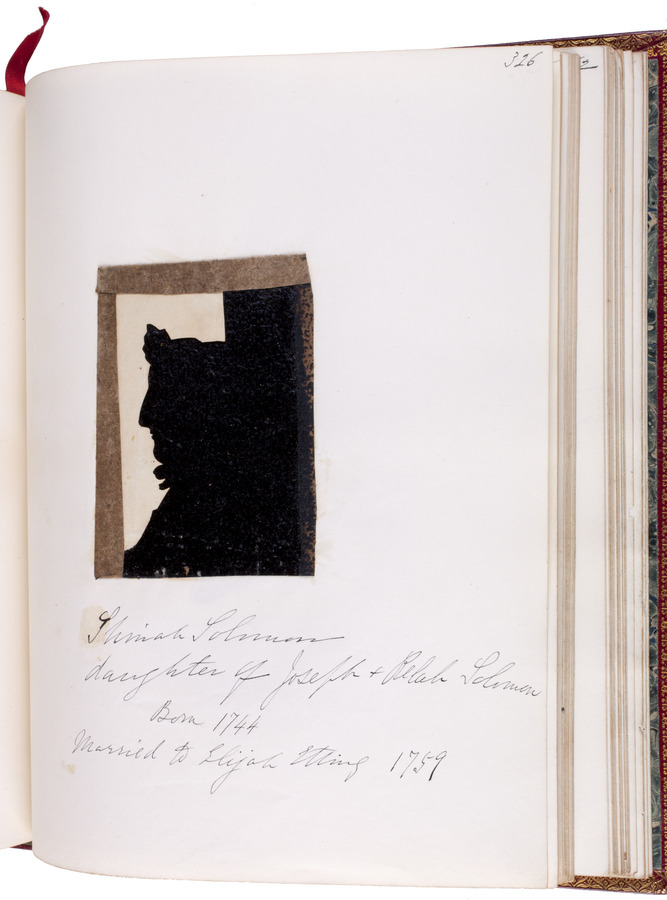

In subsequent generations, members of the Etting family sought to honor and memorialize their predecessors, and these efforts involved portraiture. There are several other visual representations of Shinah Etting, including two silhouette portraits by an unidentified artist, in the collection of the Maryland Center for History and Culture (fig. 6). These likenesses are preserved within an album that belonged to her granddaughter, Richea Gratz Etting (1792-1881), daughter of Solomon Etting and his second wife, Rachel Gratz Etting.

This volume also includes poetry, newspaper clippings, sketches, and silhouette portraits of various family members. For Richea Gratz, assembling the likenesses of her paternal grandmother, as well as her maternal grandmother, her mother, her sister-in-law, and even her infant niece would have prompted reflection on several generations of the women in her family, as well as her cultural and religious heritage.

Though the historical record offers limited information regarding Shinah Solomon Etting, it is clear that she was resilient, tenacious, and enterprising. Her portrait attests to the presence of a Jewish community (albeit a small one) in early Baltimore. The Etting family’s experience reveals both the opportunities available to Jewish people in early America and the discrimination that they faced. Furthermore, her son Solomon’s identity as both a civil rights pioneer and an enslaver further complicates this history. As we seek to expand the narrative of early America, the stories of families like the Ettings can further our understanding of the complex intersections between religious diversity, civic belonging, and enslavement.

Emily Rose Beeber is the spring 2023 Curatorial Intern for American Painting & Sculpture and Decorative Arts.

[1] Eleanor S. Cohen, “Family of Etting,” January 20, 1931, BMA Object File, 1968.14.

[2] Norman L. Kleeblatt, The Jewish Heritage in American Folk Art (New York: Universe Books, 1984), 36.

[3] Quoted in Sona K. Johnston, American Paintings 1750-1900 from the Collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1983), 131.

[4] Isidor Blum, The Jews of Baltimore; An Historical Summary of Their Progress and Status as Citizens of Baltimore from Early Days to the Year Nineteen Hundred and Ten (Baltimore and Washington: Historical Review Publishing Company, 1910), 8.

[5] “Black Marylanders 1820: African American Population by County, Status & Gender,” http://slavery.msa.maryland.gov/html/research/census1820.html.

[6] Elizabeth Lamb Clark, “Solomon Etting,” in Facing the New World: Jewish Portraits in Colonial and Federal America (New York and Munich: Prestel, 1997), 87.

[7] Solomon Etting, “Return of Solomon Etting of Lancaster,” August 11th, 1788, Lancaster History, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/return-of-solomon-etting-of-lancaster/CQFx6SsqUZL0iw?hl=en.

[8] Solomon Etting, “Ten Dollars Reward,” Federal Gazette, October 7, 1796. Though Etting’s advertisement lists her name as Darkey, the woman’s prior enslaver published a response to Etting’s notice later that year and referred to her by the name Dark. See Federal Gazette, December 14, 1796.

[9] Solomon Etting, Moses Sheppard, and Charles Howard, “To the People of Maryland,” Baltimore Gazette and Daily Advertiser, August 30, 1831.