At the 2014 Grammy Awards, the French electronic duo Daft Punk–donning their trademark spacesuits with helmets obscuring their faces–performed their hit collaboration “Get Lucky” with hip-hop producer Pharrell Williams and funk guitarist Nile Rogers alongside the legendary Stevie Wonder. The medley of hits, including Chic’s “Le Freak” and Wonders’ “Another Star”, bridged decades and genres—funk, disco, and contemporary techno.

Wearing a simple outfit of white pants rolled at the cuffs, black patent loafers, and a black T-shirt, Williams’ look was topped by a distinctive, wide-brimmed, oversized tan hat.

The hat quickly went viral and became a defining look for Williams during a high point in his career with the concurrent successes (and occasional controversies) for “Get Lucky,” Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines,” and the infectiously poppy “Happy” from the animated film Despicable Me 2.

The iconic hat worn by Williams is on view in The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century. It’s one of the more than 90 works that show how hip hop has reconstructed the contemporary canon of music, fashion, and art from the streets to runways and galleries, while becoming the most globally listened to music genre. But the hat is not only an important hip-hop artifact because of the Grammy performance. It has a long history in hip-hop fashion and an equally interesting post-Grammy afterlife.

From Punk Rock to Hip Hop

“I love to tell this story,” shares Gamynne Guillotte, Chief Education Officer. “The story goes that Pharrell was out shopping in a vintage store. He finds the hat; he likes the hat. He decides that the hat is going to become an iconic look for him.”

Then as Williams learns the hat’s hip-hop history, he becomes more invested in the look.

Thirty-two years before Willams wore it, the hat debuted in U.K. designer Vivienne Westwood’s fall 1982 Buffalo/Nostalgia of Mud collection. Westwood was a punk rock visionary who designed clothing at the London boutique SEX she ran with her then-partner Malcolm McLaren, cultivating the aesthetic we still associate with punk rock.

Music impresario McLaren, who managed punk bands The Sex Pistols, The New York Dolls, and Bow Wow Wow, was always looking for the next youth culture innovation. McLaren quickly capitalized on the emerging hip-hop scene, sampling in his 1983 hit song “Buffalo Gals” from his Duck Rock album the then-novel scratching technique of The World’s Famous Supreme Team, a DJ duo known for their New York and New Jersey hip-hop radio show. Duck Rock’s cover and liner notes were designed by Keith Haring, the pop artist who was first noticed for his graffiti line work. The song “Buffalo Gals” proved very influential—inspiring everything from Neneh Cherry’s “Buffalo Stance” (1989) to Eminem’s “Without Me” (2002).

McLaren and The World’s Famous Supreme Team also wore the “Buffalo Hat” from Westwood’s collection while promoting the album, and the hat became further embedded in hip-hop aesthetics through its appearance in films such as Wild Style (1982) and Beat Street (1984).

“What’s so fascinating,” Guillotte continues, “is Pharrell Williams didn’t initially know this history but yet still gravitated to this object, this important artifact of early hip-hop history.”

Going Viral

Thirty-two years later, having circulated from Westwood’s runway to film sets and the streets of New York City, Williams repopularized the hat.

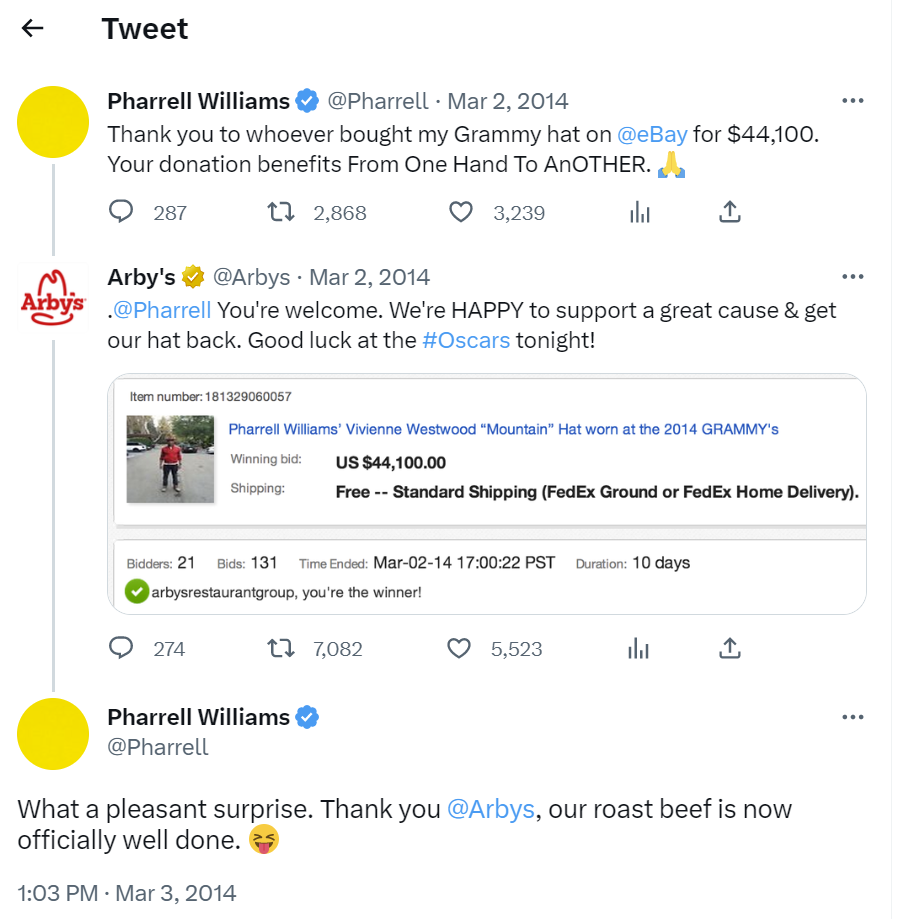

At the 56th Grammy Awards, “Get Lucky” received two Grammys that evening, but it was Pharrell’s hat that stole the show–quickly going viral. A popular meme paired Williams’ distinctive headgear alongside famous cartoon characters famous for their big hats, such as Woody from Toy Story and Smokey the Bear. A parody Twitter account @Pharrellhat sprung up before the end of the Grammy Awards, where Pharrell wore the hat all evening, paired with an Adidas original red leather tracksuit (also on display as part of The Culture exhibition). Many noted similarities to the ten-gallon logo of American fast food chain Arby’s, and the restaurant even tweeted: “Hey @Pharrell, can we have our hat back? #GRAMMYs.”

“So fast forward to us trying to find the hat,” Guillotte shares. “We know we want to have it in the show, so we go looking for the hat. Does Pharrell have the hat still? No…”

Arby’s, We Have the Hat!

“It was one of the harder things to track down, a wild goose chase,” says Carlyn Thomas, Exhibition Manager, who worked as a Curatorial Assistant for The Culture. Thomas was able to identify that the now-defunct Newseum in Washington, D.C., temporarily displayed the hat after the Grammys. Then the trail went cold from there.

Alerted to the series of Tweets by Arby’s after the Grammy Awards, The Culture’s curatorial team found out that Arby’s purchased the hat for $44,100, after Williams auctioned the hat to benefit his charitable organization From One Hand to Another.

“But you can’t just call Arby’s or email a corporation of that size and receive an immediate response,” Thomas continues.

Thomas explains that for works of contemporary art that the BMA wants to borrow for an exhibition, there are regular routes of inquiry and research when working with galleries or private collectors. Thomas says when it came to fashion pieces, they focused on contacting fashion houses such as Gucci and Louis Vuitton for particular items while other pieces of fashion ephemera were purchased on eBay.

The hat was a unique search though. The curatorial team wasn’t just finding a vintage Vivienne Westwood hat (already a difficult search) but the particular one owned and worn by Pharrell.

The curators eventually tracked down contacts in the communications and public relations teams at Inspire Brands, the umbrella company that owns and manages many of America’s fast food and casual restaurants, including Arby’s. Since 2014, the hat has resided at the Inspire Brand’s offices in Atlanta, and the team was excited to lend the hat for The Culture exhibition.

The Hat & The Culture

“If you look at the credit line, Arby’s is loaning the hat to us for the show,” Guillotte points out. “Once again, this links together some of the major themes of the show—branding, icons, and iconography—and how these shift over time from music to fashion to business brands, more generally.”

Both art and hip hop call for a set of recognizable figures, symbols, and icons to draw upon, and obscure references can show who has this insider knowledge. Guillotte shares that just as “there are Renaissance paintings that you cannot understand unless you know the biblical and mythological references, there are also works of contemporary art that refer to hip-hop artists and lyrics that you must know in order to read these works.”

Guillotte points out the parallel career trajectories of Williams and McLaren as music producers always on the cusp of the new and, through calculated self-fashioning, how they established themselves as popular, successful brands, not unlike Arby’s.

“There’s a reason Pharrell is the new creative director at Louis Vuitton, and it’s not unlike how Arby’s has continued to rebrand itself to remain popular, too,” Guillotte concludes. “There’s an interesting tension between legitimacy and brand-building and canon formation in hip hop.”

And for the iconoclasts out there, you can also purchase an Arby’s “iconic 10-gallon hat” on their website for $20.

The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century is on view now through July 16, 2023. To reserve tickets, visit artbma.org/theculture.

Co-organized by the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) and Saint Louis Art Museum (SLAM), the exhibition is co-curated by Asma Naeem, the BMA’s Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director; Gamynne Guillotte, the BMA’s Chief Education Officer; Hannah Klemm, SLAM’s Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art; and Andréa Purnell, SLAM’s Audience Development Manager.

The Culture is further supported by an advisory committee comprising experts and artists across a wide range of disciplines, including Martha Diaz, Founder and President of the Hip-Hop Education Center; Wendel Patrick, professor at the Peabody Music Conservatory at Johns Hopkins University; Tef Poe, rapper and activist; Hélio Menezes, anthropologist and curator of Afro-Atlantic Histories; and Timothy Anne Burnside, public historian and Museum Specialist in Curatorial Affairs at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

This exhibition is generously supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Additional support is provided by The Alvin and Fanny B. Thalheimer Exhibition Endowment Fund, the Victor J. Schenk Trust, Patricia Lasher and Richard Jacobs, Lorayne and Jim Thornton, and Clair Zamoiski Segal.

Beats, rhymes, culture and finances for this exhibition are generously provided by hip hop ambassadors “DJ Fly Guy” Flynn & Nupur Parekh Flynn, inventor of BAGCEIT®