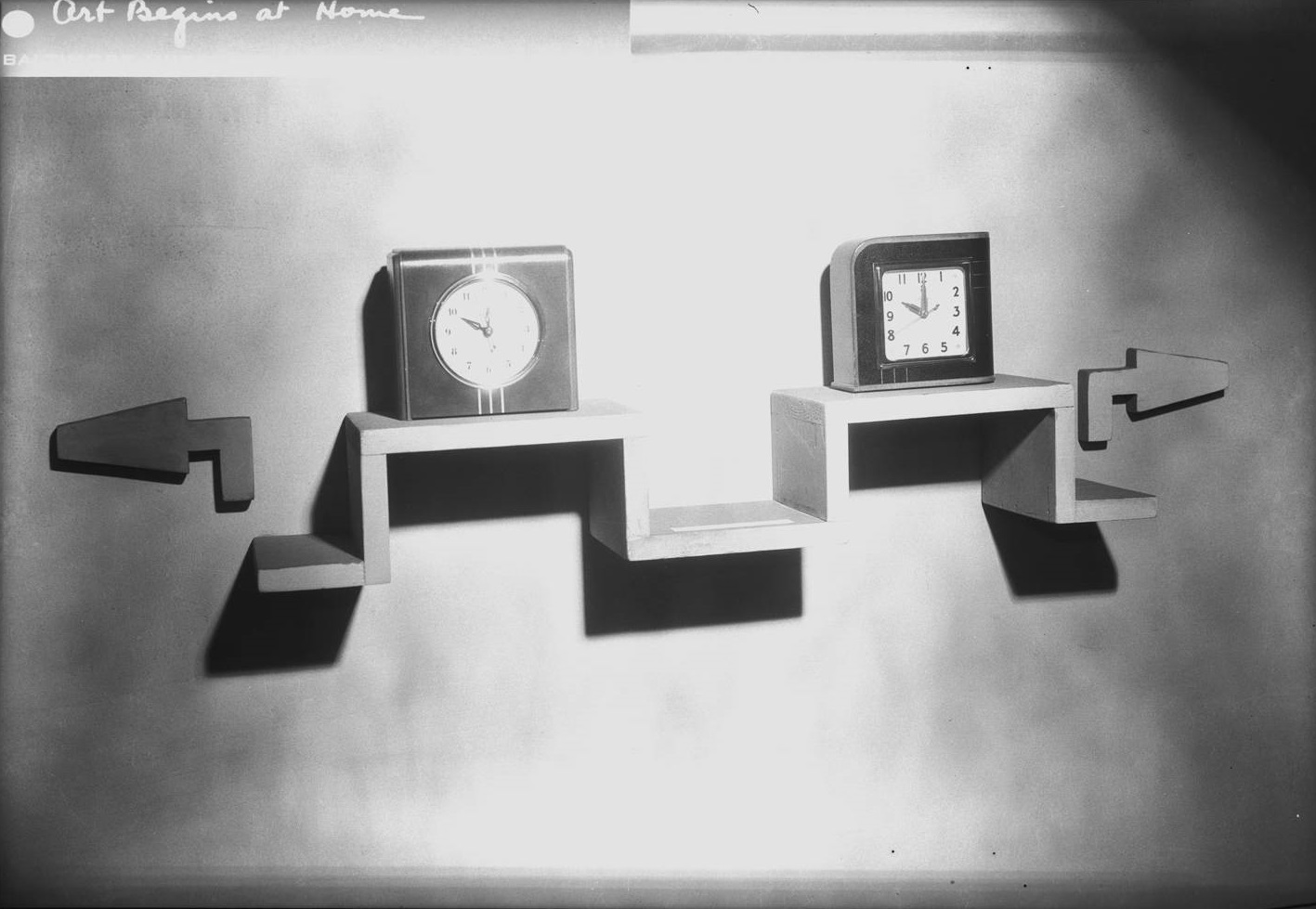

You’re standing in a maze inside the BMA, looking at two clocks. One has a round face inside a square frame with three lines running down its center. The other has a square face and square frame with one curved corner. Which one represents good design?

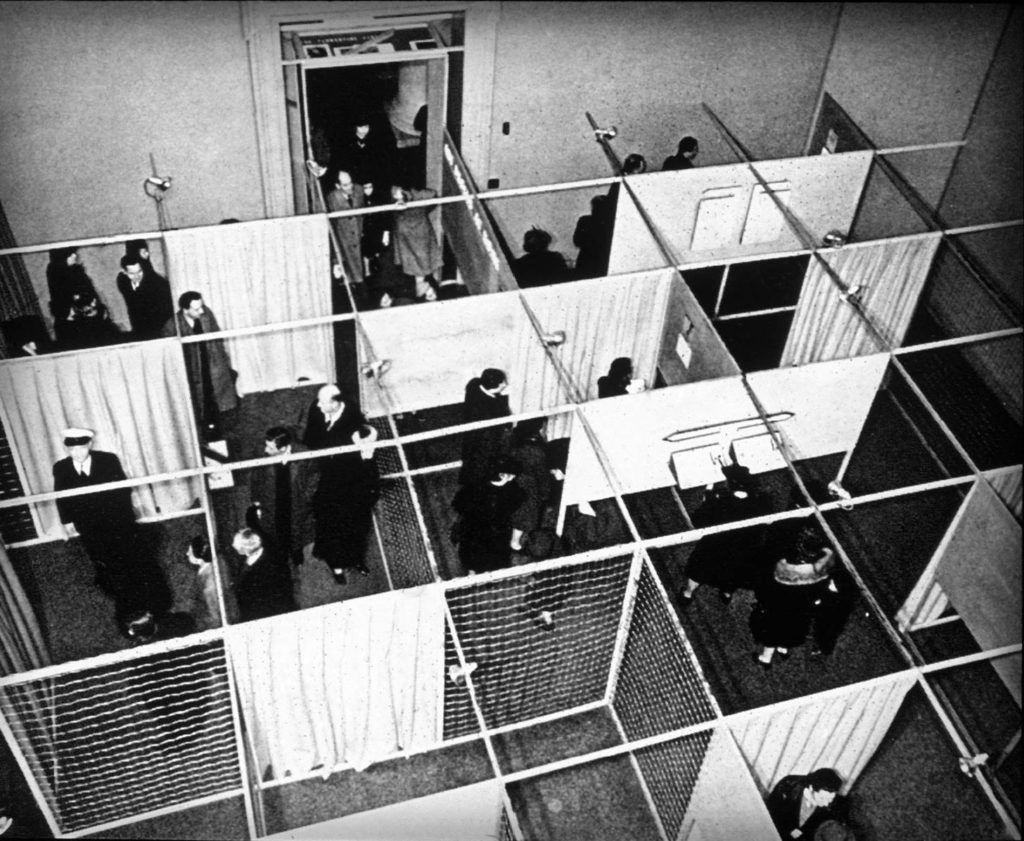

Your answer could bring you one step closer to the finish and validation or send you doubling back into the BMA’s experiment, Art Begins at Home, after reading why your choice was ‘wrong’.

The Museum built this labyrinth in 1940 to inform visitors about decorative arts, from wallpaper and silverware to ashtrays and lamps. It sounds as eccentric today as it would have in 1940. How and why, then, did the BMA conceive of this odd museum experience?

The impetus for Art Begins at Home is in the work of Henry

On Labor Day 1938, the Museum opened the first exhibition created as a direct response to the results of its survey. Labor in Art aimed to make art feel relevant to the community by showcasing paintings, drawings, and prints depicting the “working man.” A crowd of over 2,500 attended the opening ceremony for Labor in Art. Throughout the 1938-1939 season, the Museum’s exhibitions continued to reflect the results of the survey. Thematic exhibitions exploring aspects of religion, sports, and patriotism were mounted as well as one of the first exhibitions of black artists in the United States by a major museum. Titled Contemporary Negro Art, the exhibition displayed works by 29 artists, including Jacob Lawrence, Hale Woodruff, and James

The Museum did not begin to experiment with the form of their exhibitions until Director Leslie Cheek Jr. was hired in 1939. Under his leadership, exhibitions and programs were not only designed to educate but to get people talking. Art Begins at Home’s unique structure took the interest in decorative arts indicated by the survey and attempted to make it provocative. Visitors were expected to wind their way through the maze, congratulating themselves on their own good taste when “correct,” exclaiming indignantly when trapped in a dead-end and forced to read why their decision had been “wrong,” and, possibly, debating animatedly with one another throughout.

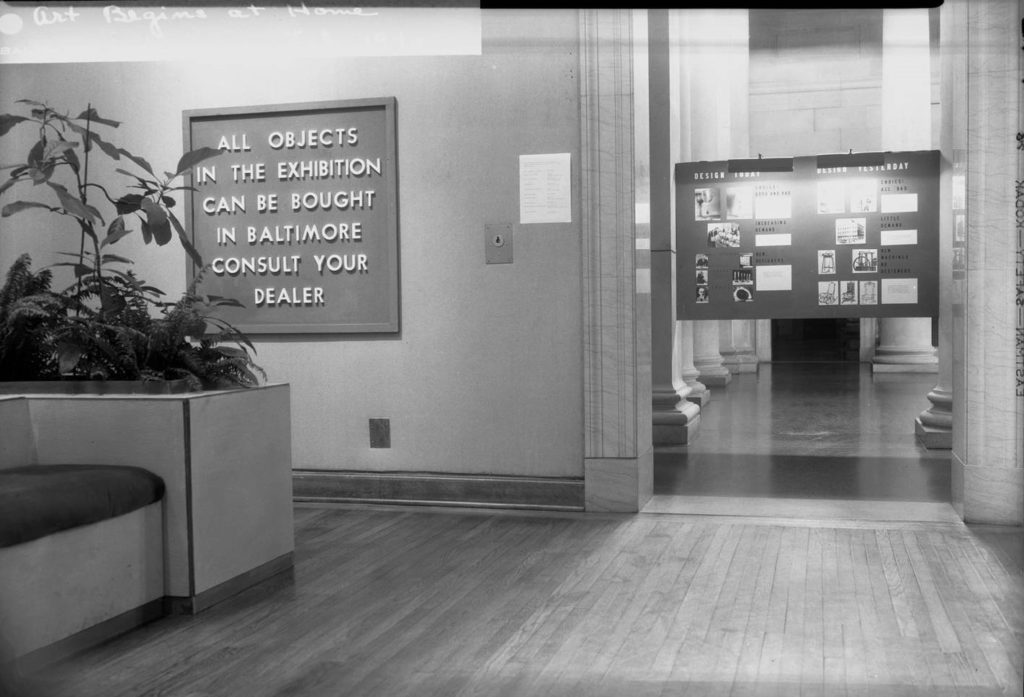

Also unique was the Museum’s commercial focus on Baltimore. After each “correct” choice, visitors would see three similar objects available for purchase at three different price points. All objects came from Baltimore craftsmen and were affordable for the average Baltimorean. By keeping their focus on Baltimore-based products, the Museum hoped to create an exhibition that would feel relatable and relevant to their local community. These examples of “tasteful” objects were intended to lead Baltimoreans to recognize and acquire well-designed items in their daily lives.

“Taste is rarely God-given. It is usually acquired, and it is acquired by honestly enjoying what one honestly likes … “

The results of the 1937 survey prompted the BMA to try to reinvent its relationship with the Baltimore community. But in order to draw interest, did the Museum make a misstep with Art Begins at Home? Interestingly, one year before the exhibition, Baltimore historian Gerald W. Johnson wrote in the BMA members’ magazine: “Taste is rarely God-given. It is usually acquired, and it is acquired by honestly enjoying what one honestly likes … What the average American needs is not ready-made taste, delivered to him like a prefabricated house. What he needs is guts enough to revolt against his mentors and go out and build his own.”

Inspired by the Treide Survey, the BMA has launched a new survey called Make It Now. We are asking 300 organizations—including schools and civic, social, and religious groups—how Baltimore’s largest art museum could better serve the people of Baltimore. This initiative will guide future exhibitions and programs. You can take the survey here.