Since its emergence in the 1970s, hip hop has grown into a global phenomenon, driving innovations in music, fashion, technology, and visual and performing arts. Coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the birth of hip hop, The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century captures hip hop’s extraordinary influence through more than 90 works of art and fashion by established and emerging artists, design houses, streetwear icons, and musicians. Asma Naeem, BMA Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director, explores hip hop’s ever-expanding reach and the role art museums must play in support of the canon in the exhibition catalog’s leading essay excerpted below.

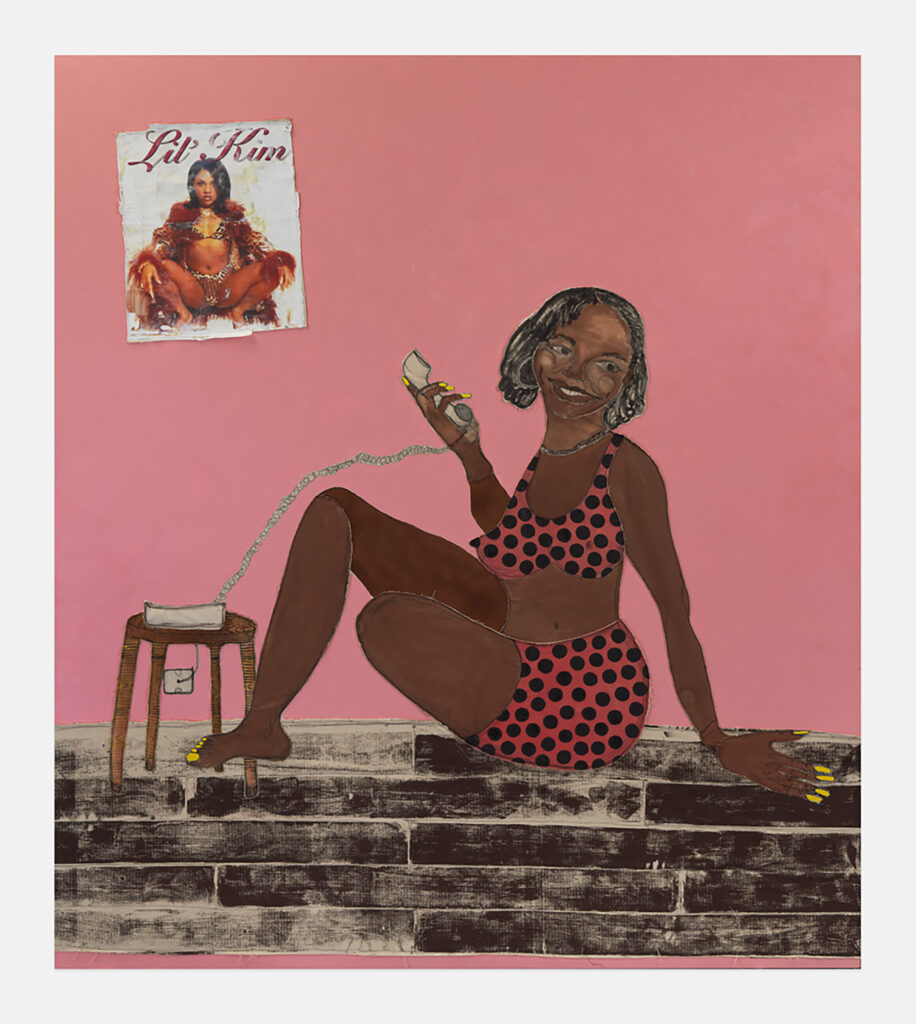

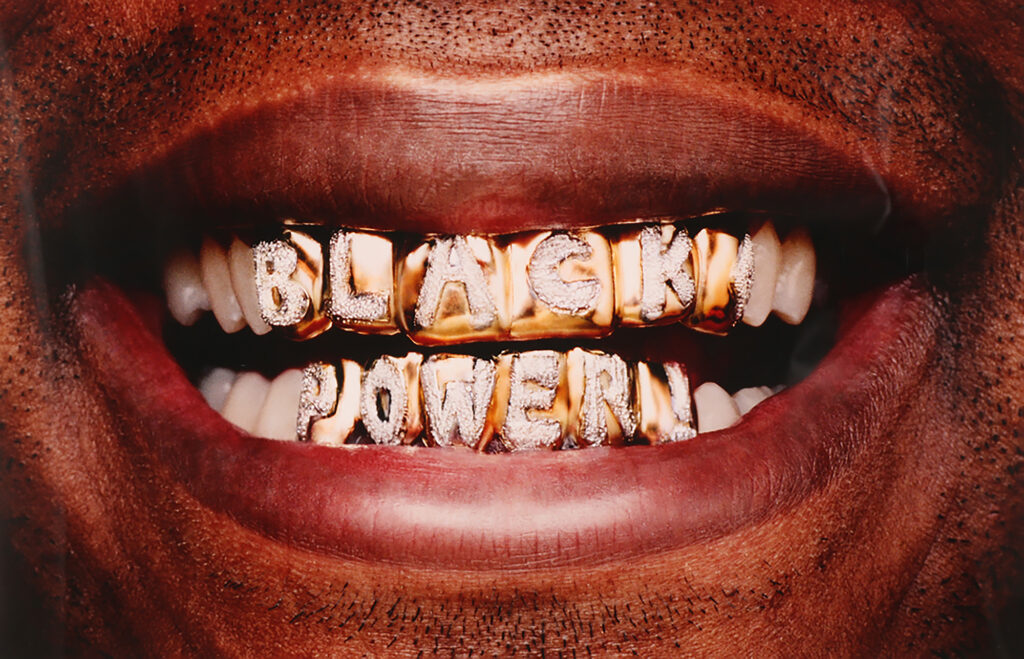

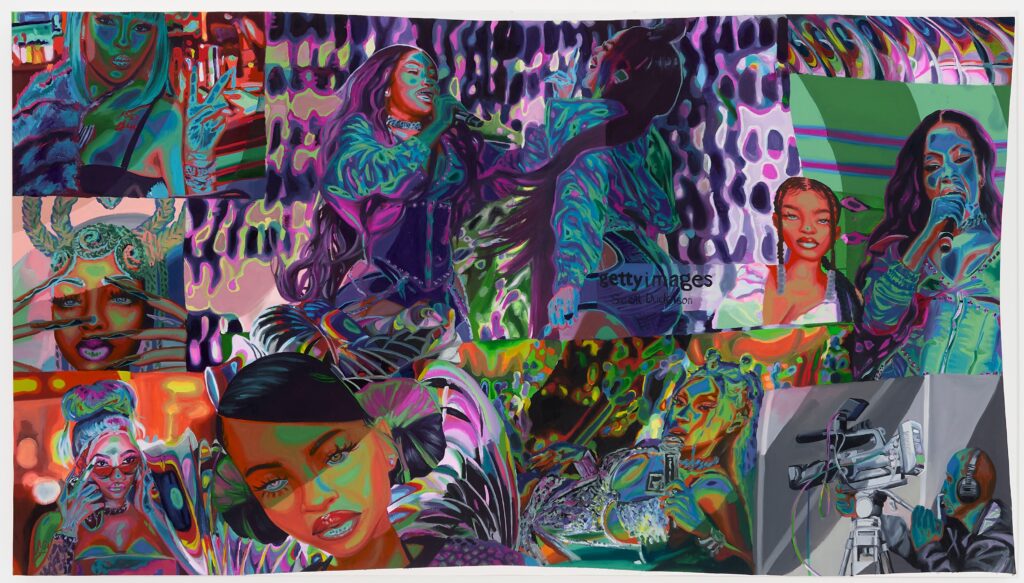

Over its now 50-year trajectory, hip hop has evolved: once rooted in the Black and Latinx youth experience and its hyper-local origins at a Bronx house party thrown by Kool Herc and his sister Cindy Campbell in 1973, it is now the most streamed form of music. Growing out of dancehall and dubstep, celebration and joy, along with a make-do-with-whatever-is-at-hand creative approach, hip hop began its blaze as a movement with four pillars: breakdancing, DJing, MCing, and graffiti. (A fifth pillar of social consciousness was later added.) Throughout the decades, rap has expanded its scope, exploring themes including civil rights and protest with such pioneering songs as Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message” (1982); criminality and the gangsta lifestyle with groups like N.W.A. and DMX; male vulnerability and bravado in the lyrics of Tupac Shakur and Gucci Mane; celebrity status and conspicuous consumption with such icons as Lil’ Kim and Pop Smoke; female liberation and sexuality through Nicki Minaj and Megan Thee Stallion; and more recently the blurring of club, dance, house, and R&B in the work of Drake and newcomers like Bandmanrill.

To those contemporary art lovers who may think that when it comes to a conversation about hip hop, they can sit this one out, I will say the following: Many of the most compelling visual artists working today are directly engaging with central tenets of this canon in their practices, in both imperceivable and manifest ways. I am not just talking about the underground legacy of graffiti and the affordability of such things as spray paint, or the appropriation of such collage-like tactics as sampling and remixing, or the in-your-face bravura of rapping, or the ecstatic finessing and posing that is breakdancing. In contemporary art today, whether through the poetics of the street, the blurring of high and low, the reclamation of the gaze, the homage to hip-hop geniuses, or the experimental collaborations across such vastly disparate fields as painting, performance, architecture, and computer programming, the visual culture of hip hop along with its subversive tactics and its tackling of social justice surface everywhere in the art of today. For many visual artists, hip hop has enabled a radical interrogation of such previously stable and homogenously white aspects of art history and culture as strategies of representation, genius, and who is the beholder. I would go so far as to say that with hip hop’s mind-blowing migration from the margins to mainstream popular culture, we are in the midst of a second Pop art movement—one that is far more layered, polyphonic, commodified, sustained, and frankly, popular—than the one in the 1960s that Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, and others developed.

Here’s another thing: Until now, visual art reflecting the culture of hip hop has been primarily limited to moving between artists’ studios and auction houses, galleries, and private collections. Art museums have largely stayed silent when it comes to acquiring these works, in a tacit and sometimes not-so-tacit disapproval of the subject matter, the vernacular syntax and materials, or the embedded values. This is to say nothing about the questions of artistic excellence and mastery that continue to be whispered among certain gatekeepers. Jamaican philosopher Sylvia Wynter, in her reflections of race and colonialism, wrote that we need to give humanness a different future, and that our current system of knowledge cannot hold the changes that are occurring and arising.1 For me, hip hop is not only part of this discourse about the future of humanness, but is also actively reshaping it, creating a new system of knowledge. This exhibition articulates these consequential stakes as well as signals how art museums need to step up beyond showcasing the work of such designers as Virgil Abloh for Louis Vuitton in temporary shows, which is an all-too-safe way to bring in crowds without devoting long-term resources or making the cultural commitment of acquiring works for their collections.

To put it simply, as vital civic and cultural centers of humanness, art museums need to embrace the culture. Objects of artistic excellence—paintings, sculptures, assemblages, fashion, wigs, and whatever else—shaped by the culture and canon of hip hop need to be placed permanently in the hallowed spaces of museums, alongside the Delacroixes, Géricaults, and DaVincis.

Notes

1. Sylvia Wynter and Katherine McKittrick. “Unparalleled Catastrophe for Our Species? Or, to Give Humanness a Different Future: Conversations,” In Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis, edited by Katherine McKittrick. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015, 9-89.

The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century is on view April 5-July 16, 2023. Visit artbma.org/culture to purchase tickets.

Co-organized by the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) and Saint Louis Art Museum (SLAM), the exhibition is supported by an advisory committee comprising experts and artists across a wide range of disciplines, including Martha Diaz, Founder and President of the Hip-Hop Education Center; Wendel Patrick, professor at the Peabody Music Conservatory at Johns Hopkins University; Tef Poe, rapper and activist; Hélio Menezes, anthropologist and curator of Afro-Atlantic Histories; and Timothy Anne Burnside, public historian and Museum Specialist in Curatorial Affairs at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

This exhibition is generously supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Additional support is provided by The Alvin and Fanny B. Thalheimer Exhibition Endowment Fund, the Victor J. Schenk Trust, Patricia Lasher and Richard Jacobs, Lorayne and Jim Thornton, and Clair Zamoiski Segal.

Beats, rhymes, culture and finances for this exhibition are generously provided by hip hop ambassadors “DJ Fly Guy” Flynn & Nupur Parekh Flynn, inventor of BAGCEIT®