When Virginia Anderson, Curator of American Art, came across Maria Hamel Finkelstein’s 1937 painting Meditation in storage, it was clear the painting had been untouched for quite some time.

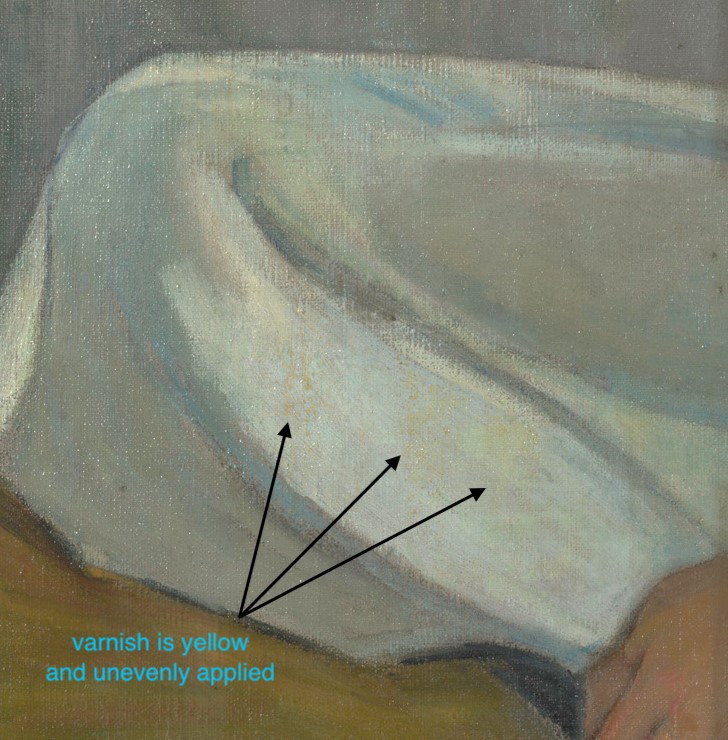

Dirt covered the surface of the painting, concealing its true colors and nuances. A thick, uneven coating of yellowing varnish created scattered splotches. There were fraying fibers along the edges of the canvas, unstable cracks in the paint, and chips of paint flaking off the surface.

Maria Hamel Finkelstein’s “Meditation” before treatment

Maria Hamel Finkelstein’s “Meditation” after treatment

Very little is known about Finkelstein’s career. Most of her artwork is unaccounted for and few descriptions or reviews of her drawings and paintings exist. This omission helped spark the research behind the new exhibition By Their Creative Force: American Women Modernists, which displays works by women artists in the BMA’s collection. The exhibition celebrates these artists’ contributions to Modernism and also critiques their exclusion from the canon.

While there are some well-known names in the show like Elizabeth Catlett and Georgia O’Keeffe, there are also artists like Maria Hamel Finkelstein (1891-1975), whose names and works have been lost to time.

Related: Preserving the Legacies of Women Artists

To learn more about Finkelstein, Sarah Cho, Curatorial Assistant in American Art, dug through the Maryland Historical Society’s archives. She found a CV handwritten by Finkelstein that shed light on the early part of the artist’s career. Born in France, Finkelstein attended the École des

While the history of Maria Hamel Finkelstein’s life and art remains murky, her painting, Meditation, is now being recognized and revealed to the public.

After World War I, Finkelstein moved to the United States with her American husband and attended the Corcoran Art School and the Maryland Institute. Traveling frequently between Baltimore and Paris, Finkelstein’s works were included in the Paris Salon, Grand Palais, the BMA’s Maryland Artist exhibitions, as well as in numerous other Maryland galleries.

The few existing exhibition records reveal Finkelstein’s interest in still lifes of flowers, portraits, and studies of nude female figures. She worked in many mediums, including charcoal, ink and watercolor, and oil paint. While the history of Maria Hamel Finkelstein’s life and art remains murky, her painting, Meditation, is now being recognized and revealed to the public.

To prepare the work for display in By Their Creative Force, conservators devised a treatment plan to first stabilize the damage and to showcase the artist’s aesthetic intention.

Conservation Technician and Pre-Program Intern, Tamsin McDonagh, began by removing the dirt, which distorts the authentic colors of the paint, obscures details, and may undergo chemical reactions with the oil paint that can degrade the painted surface.

McDonagh then used an aqueous, or water-based

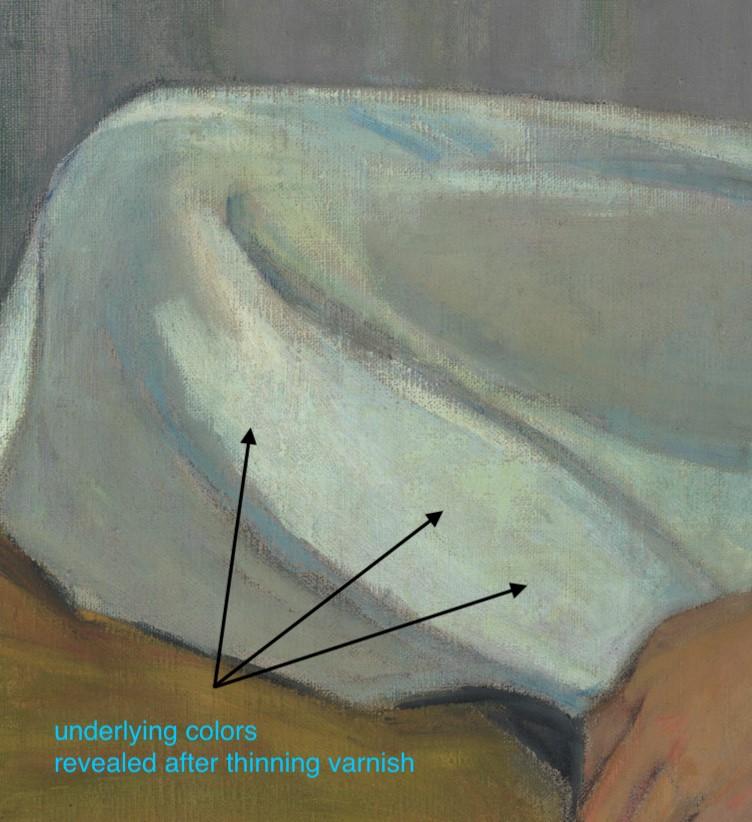

It took several weeks to clean with so much dirt and grit, but the results were dramatic. Nuances in the brushwork, variations in Finkelstein’s palette, and subtle highlights were finally revealed.

To slow down future degradation, conservators applied small amounts of an acrylic aqueous adhesive to vulnerable areas of paint under a microscope. The adhesive anchors loose chips of paint to the surface, seals off edges of cracks so they don’t spread, and holds frayed canvas fibers in place.

After stabilizing the paint, conservators examined the varnish under Ultraviolet (UV) light—a type of light you can’t see, but makes certain materials fluoresce or “glow.” The yellow coating fluoresced a milky yellow, which indicated a natural resin varnish. Identifying the type of varnish on a painting enables conservators to safely remove it without unintentionally stripping the underlying paint layer. McDonagh applied various solvents in small test areas along the edge of the canvas to find one that was safe and effective in removing the yellow varnish. She then wetted cotton swabs with this solvent and carefully wiped the surface to thin out layers of varnish that were thick and visually distracting.

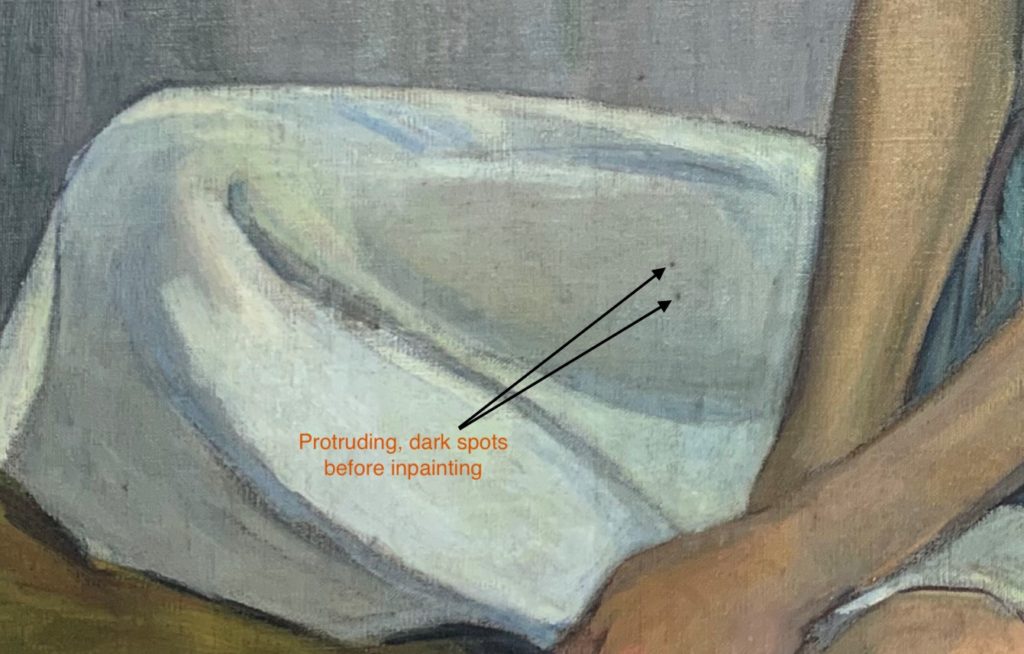

The final step was to inpaint or retouch the canvas with paint to reestablish its visual integrity and unity. Inpainting makes areas of loss or deformation in the paint less visible. McDonagh inpainted several protruding dark spots on the surface of Meditation to minimize their impact on the viewer. Reversibility is an important ethical tenet of conservation, so chemically stable, easily removable paints were used, in case conservators needed to alter the inpainting in the future.

Like other Modernist artists, Finkelstein used underlying geometric shapes that contrast with the organic, curved lines of the figure, softening the composition. Highlights on the figure’s hands, eyelids, and dress produce a subtle brightness that evokes a sense of spirituality and grace, creating a quiet tension for the viewer as they look in on the figure’s private moment.

Before its cleaning, dirt muddied the painting’s original colors and prevented a proper look at Finkelstein’s handiwork. The cleaning brightened the image and revealed a multitude of colors that add depth and subtlety, evoking a spiritual and thoughtful mood. Removing dirt and varnish also revealed the quick and light manner in which Finkelstein painted, recalling her love of watercolors. Its cleaning and conservation allow us to see Finkelstein’s intentions more clearly, affecting our interpretation of Meditation.

This conservation treatment preserves a previously overlooked

work for future generations so that Finkelstein may be added to the narrative

of American Modernism. Reflecting on the title of her work, Finkelstein’s Meditation makes us confront why so

little is known of women artists who were once key figures in the art world,

how conservation can play an integral role in understanding art, and how we

choose to recount and interpret the past as we move forward.

By Their Creative Force: American Women Modernists is on view through July 5, 2020.

Authors: Sarah Cho, Curatorial Assistant in American Art, and Tamsin McDonagh, Conservation Technician and Pre-Program Intern