For the current exhibition Histories Collide: Jackie Milad x Fred Wilson x Nekisha Durrett, on view in the John Waters Rotunda and adjacent galleries, Washington, D.C-based artist Nekisha Durrett turned to the legacy of Harriet Tubman for her installation Frontier.

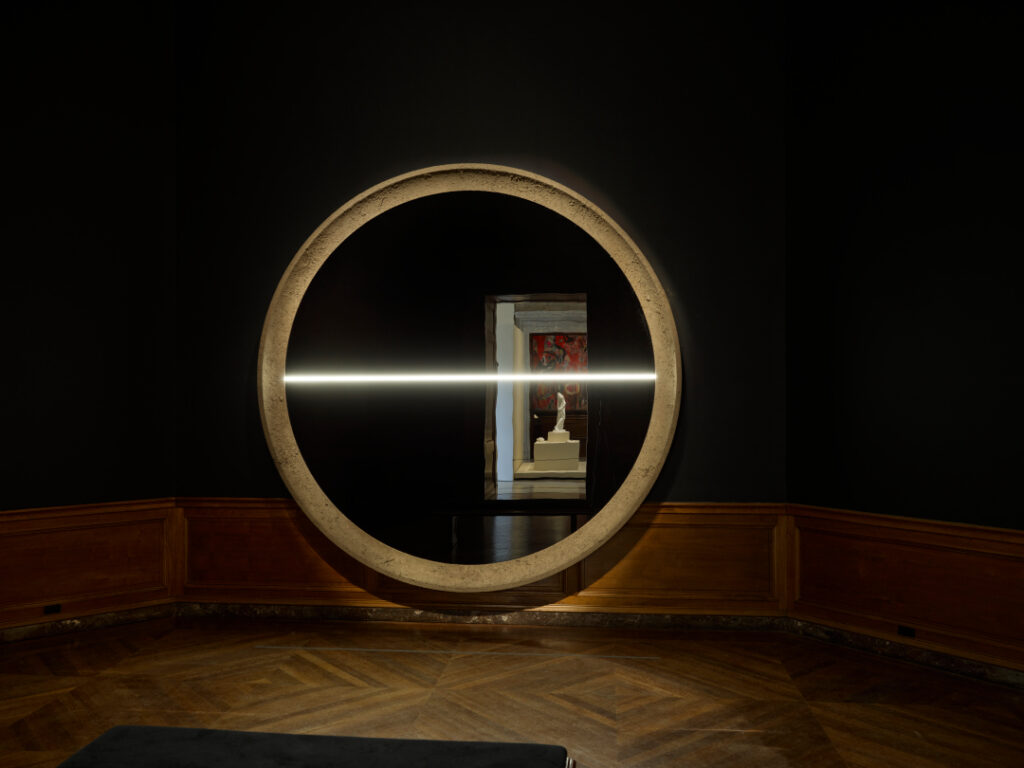

Instead of a traditional portrait of Tubman, Durrett has produced an abstract study of Tubman’s revolutionary and visionary way of thinking. Entering the darkened gallery space, we encounter a 14-foot black reflective circle created from an acrylic panel bisected by an LED line of white light and ringed with soil. You may see your own reflection and the artworks of Fred Wilson and Jackie Milad mirrored back, too.

Like so many of Durrett’s works, the piece converses with specific local histories, and erased and misrepresented Black histories.

Historical Heroes

Durrett, a multimedia artist and arts educator based in Washington, D.C., has long considered Fred Wilson one of her heroes. As a former teacher in the Museum Studies Department at Duke Ellington School of the Arts in D.C., Durrett taught courses in digital media, cultural studies, curatorial skills, and art history, and incorporated Fred Wilson’s methodologies into her classes.

“Fred Wilson teaches us that we don’t have to take these histories that we encounter on field trips and museums at face value,” she shares. “We taught the students to challenge history, to turn on the light to see more, and to bring our own heroes forward into the light.”

In her multimedia works found through the greater Washington, D.C. to Baltimore metro area, Durrett often tells precise and deeply researched local histories.

In Arlington, Virginia, her tribute to “Queen City,” a Black neighborhood that was razed to make way for the Pentagon and connected roadways, opened this May. The 40-foot tall brick tower has 903 blue waterdrop ceramics suspended from the interior walls—created by Black ceramicists and makers from across the country as a collaborative project, including Martha Jackson Jarvis and her daughter, the artist Njena Surae Jarvis. Each ceramic represents a resident displaced by the U.S. government wielding eminent domain in the name of progress. She’s also created an expansive mural celebrating D.C.’s distinctive musical genre Go-Go for an event at the Smithsonian, and her works are found throughout the area’s libraries and art galleries.

“The stories of people just living their lives get overlooked or lost in these big grand narratives,” Durrett says about the histories she tells in her artwork. And sometimes, her artwork turns to major figures—such as Harriet Tubman—to tell a different story, too.

“She Contains the Vastness of the Universe”

“Harriet Tubman once had this vision of a white line, an astral projection,” Durrett explains of her enigmatic sculpture inspired by Tubman’s prophetic visions.

“[To me,] on the one side of the white line there is suppression and then on the other side is freedom, but that line keeps moving,” Durrett says. “[Tubman was] seeing beyond that line. She’s looking at that viewer in the future. That’s what I am trying to portray in this piece.”

In Sarah Hopkins Bradford’s widely read 19th-century biography Scenes from the Life of Harriet Tubman (1869), the author, a white woman, described Tubman’s “ignorant, dark mind.”

This belittling depiction did not make sense to Durrett; Tubman was an organized tactical thinker, able to navigate halfway across the country while protecting the lives and securing the freedoms of others. Yet, in historical narratives, Durrett read over and again that the lens through which white authors depicted Black leaders filtered and distorted the truth with their own biases. Hopkins Bradford seemed to insert herself into Tubman’s vision in passages that especially struck Durrett, like this one:

“In my dreams and visions, I seemed to see a line, and on the other side of that line were green fields, and lovely flowers, and beautiful white ladies, who stretched out their arms to me over the line, but I couldn’t reach them no-how. I always fell before I got to the line.”

“Well, how much of that vision is true?,” Durrett asks. “We don’t really talk about the complexity and depth of mind of our heroes. The biographer tried to reduce [Tubman’s] mind to darkness and ignorance, but she contains the vastness of the universe.”

In addition to the glowing white line and reflective black surface of Frontier, the circumference is ringed with soil collected at the root of a tulip poplar known as the Witness Tree at Mt. Pleasant Acres Farms in Preston, Maryland, with permission from its stewards, Paulette Greene and Donna Dear. Tubman was born into slavery near this site and escaped in 1849. She returned in 1854 to rescue her father Ben, a free laborer, and her enslaved brothers Ben, Robert, and Henry.

“It was a missed opportunity that my teachers didn’t mention to me that Harriet Tubman grew up so close, and the very same soil that we played on as kids was very similar to the soil that maybe Harriet Tubman played on when she was a kid. And then when she became an adult, it was the same soil that she walked while leading 70 or so Black individuals to freedom,” Durrett explains about her chosen medium.

“I think that we all possess these capacities of so-called heroism. It’s just a matter of listening to that inner voice and believing that the power resides in you,” Durrett concludes. That is why the work reflects back one’s own image, she asserts. “And that soil is a brilliant unifier. The same soil that’s here right now is the same soil that was here millions of years ago is pretty powerful: it carries with it all these histories at once.”

Follow Nekisha Durrett on Instagram @nekishadurrett and online at nekishadurrett.com

Histories Collide: Jackie Milad x Fred Wilson x Nekisha Durrett is on view through March 17, 2024.

The accompanying article about Jackie Milad may be read here: “Jackie Milad Confronts Museums’ Complicated Histories.”

Associate Curator of Contemporary Art Cecilia Wichmann and Dave Eassa, former Director of Public Engagement, co-curated the commission and exhibition. A jury of distinguished cultural workers, including Angela N. Carroll, Teri Henderson, Ashley Minner Jones, and Ginevra Shay, consulting with George Ciscle as the jury’s advisor, selected proposals by Durrett and Milad for commission.

A shorter version of this article appeared in the winter/spring 2023 issue BMA Today, the Members’ magazine published three times a year.