Baltimore-based artist Jackie Milad has created four new works for the exhibition Histories Collide: Jackie Milad x Fred Wilson x Nekisha Durrett, currently on view in the John Waters Rotunda and adjacent galleries.

Milad’s works reconcile and collage together the histories of ancient Egyptians and ancient Americans, her family history, and contemporary culture—from pop culture references to the cultural touchstones of 21st-century Egyptian, Egyptian-diasporic, and Central American peoples.

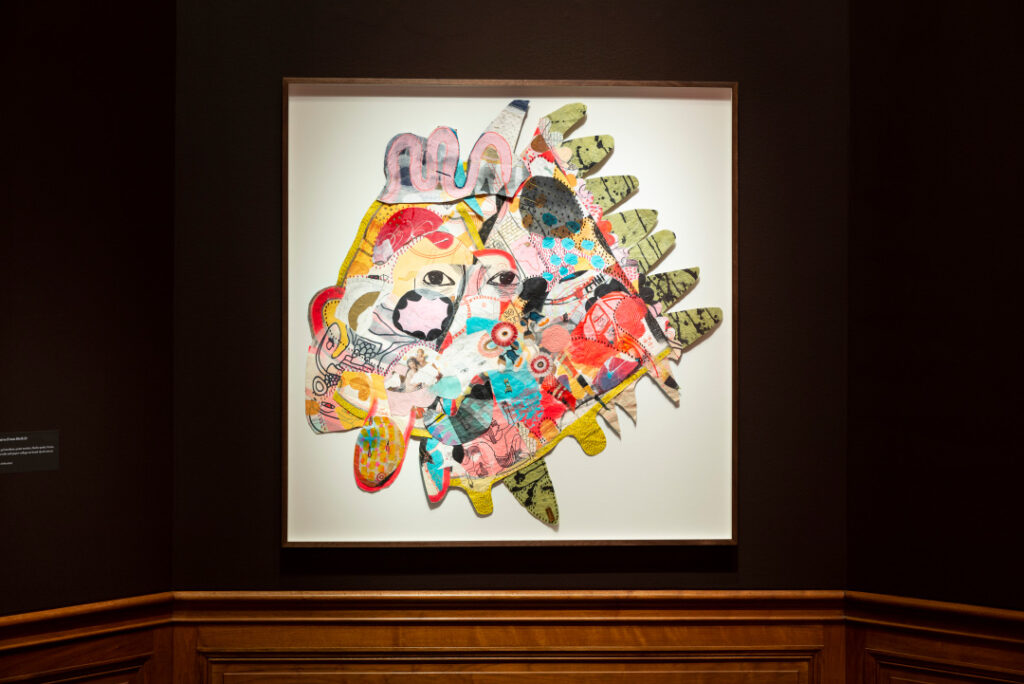

Two large-scale collaged paintings, Shabti Emerge and Unwrapping, Unrolling, incorporate acrylic, brass, mixed textile, paper collage, and other materials on hand-dyed canvas with tea, each measuring approximately 10-by-11 feet. She has also created To Destro (Birth 3), a cut-out, collage and fabric painting, as well as a 15-inch bronze serpentine statuette entitled Wadjet. The titles allude to both her Egyptian heritage and artist Fred Wilson’s Artemis/Bast. Shabti are funerary figurines found in tombs and pyramids, while Wadjet is one of the oldest of Egyptian deities, the goddess of serpents.

Who Owns Egyptian Antiquities?

Growing up in Baltimore, Milad fondly recalls visiting the city’s art museums with her mother, an art lover, as a child. “The BMA and the Walters were both really important to me, but I also had a lot of family in New York City and going to the Met was really part of my upbringing, too.”

In fact, it was the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s expansive collection of ancient Egyptian works that first inspired Milad to consider the histories of collecting Egyptian antiquities for her BMA proposal. “There are over 350 institutions across 27 countries that have Egyptian objects,” the artist explains.

“But I wanted to go to the source of where this mentality of collecting ancient Egyptian and Egyptian heritage begins: The British Museum,” Milad shares. “The British Museum [alone] has over 100,000 works of Egyptian art, the largest collection of ancient Egyptian objects outside of Egypt. The scale of the collection is just mind-blowing.”

For Milad, the complicated history of museums allows for crucial contemporary discussions about ownership, repatriation, rectification, and the necessity of bringing in the voices, experiences, and expertise of Egyptian and Egyptian diasporic scholars and artists, such as Milad, whose parents emigrated to the U.S. from Egypt (father) and Honduras (mother) in the 1970s.

During her research at the British Museum and in England, Milad has worked with Dr. Heba Abd El Gawad, an Egyptian-British archaeologist at the University College London Institute of Archaeology, having exactly these types of conversations. “She asks those questions: How has this dispersal of heritage affected the current contemporary people of Egypt?”

The collecting of historical Egyptian objects in 17th and 18th century England, Milad notes, was not about preservation and curation as much as conquest, a colonial treasure hunt, showing England’s imperial dominance through the looting and desecration of sacred burial spots. This includes problematic practices then and now, such as the historical European custom of grinding and repurposing of mummified remains whether for art“—mummy brown” painting pigment, or medical reasons—digestible and supposedly healing “mummia.” Begun during the “Enlightenment” era, the display of mummified remains is one of the contested practices still widely practiced in museums worldwide. Milad believes that museums still often neglect the contributions of living artists of the Egyptian diaspora and often fail to make meaningful connections with Egyptian viewers.

“When you go to the Met or the British Museum, it’s all siloed and even taken out of world history. For me, it’s a very disconcerting thing,” Milad says. “Going into these spaces, there’s a feeling of ‘it’s yours, but it’s not yours.’ There’s a very disconnected experience and a real missed opportunity for museums to connect.”

Collaging Family Histories & Contemporary Allusions

Milad initially studied fashion at Parsons, then switched to jewelry design, following in the goldsmithing footsteps of her father, her brothers, and several generations of her family. She later embraced a diversity of artistic expressions—such as performance art and painting—when she studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University. She continued that interdisciplinary approach at Towson University, where she earned her M.F.A., and in her teaching at MICA.

In her practice, she synthesizes all of this—mixing media, interworking fabric, constructing jewelry, and more. Her works incorporate ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and ancient American figures, as well as pictures and letters from her family.

But irreverent pop culture references, fragments of poems, and contemporary aesthetics also inform her works. The street graffiti in Cairo created by young protestors. Punches of hot pink. Hip-hop and global music lyrics. Milad is also deeply inspired by Baltimore’s vibrant creative community, which she deems as “experimental, exciting, dynamic.” These all swirl their way into Milad’s collages.

For the BMA exhibition, Milad has collaborated with her family: her young son has contributed marks, and Milad’s goldsmith father has fabricated brass medallions for the exhibition, sewn into her collaged-paintings. Milad designs the icons based on ancient artworks from her ancestors’ cultures, linking past and present, family and history.

“This puts the icons and objects into a new context that I have control over,” Milad says. “There’s so much to think about when using these [historical] objects. When I draw out my icons, I have a feeling like, ‘I’m going to take care of you.’”

Follow Jackie Milad on Instagram @ _jackie_milad_ and online at jackiemilad.com/home

Histories Collide: Jackie Milad x Fred Wilson x Nekisha Durrett is on view through March 17, 2024.

The accompanying article about Nekisha Durrett may be read here: “Imagining Harriet Tubman’s Visionary Being with Nekisha Durrett.”

Associate Curator of Contemporary Art Cecilia Wichmann and Dave Eassa, former Director of Public Engagement, co-curated the commission and exhibition. A jury of distinguished cultural workers, including Angela N. Carroll, Teri Henderson, Ashley Minner Jones, and Ginevra Shay, consulting with George Ciscle as the jury’s advisor, selected proposals by Durrett and Milad for commission.

A shorter version of this article appeared in the winter/spring 2023 issue BMA Today, the Members’ magazine published three times a year.