A fifty-year career retrospective of one of the most significant artists of our time

“I actually believe art is one of the engines causing the Earth to rotate.” —Joyce J. Scott

Mentor and matriarch, consummate artist, avowed trickster, and always an inspiration: Joyce J. Scott has spent five decades creating dazzling, genre-defying art, fostering creative communities, collaborating across generations and disciplines, and confronting injustice with beauty, grace, and humor.

The summative career retrospective Joyce J. Scott: Walk a Mile in My Dreams, co-organized with the Seattle Art Museum, features nearly 140 examples from the artist’s expansive career—including sculpture, garments and jewelry, performance footage, and ephemera from Scott’s personal archive, tracing the history of her practice through ten thematic sections.

In the first gallery, visitors will encounter a newly commissioned installation: The Threads That Unite My Seat to Knowledge. In this “habitat for the soul,” Scott shares familial histories in a storytelling environment of heirloom quilts. Working with collaborators Espi Frazier, Pamela Li, Randi Reiss-McCormack, and Teresa Sullivan, Scott adorned this structure with crochet and beadwork. On surrounding walls, story quilts and beaded tapestries create an imaginative landscape, while figurative sculptures “offer wisdom” at the four corners of the room.

Baltimore Roots and Global Wings

Born and raised in Baltimore, Scott earned her BFA at MICA. Her mother, the artist Elizabeth Talford Scott (whose artworks are also exhibited at the BMA and across Baltimore this spring), encouraged Scott’s identity as an artist from childhood. Scott learned to make the things necessary for daily life—clothing, quilts, and her home environment—into beautiful artworks by recycling, salvaging, and creating anew from discarded materials.

She also learned a cooperative, egalitarian ethos which evolved and grew as she traveled the world. During her graduate studies at the Instituto Allende in Mexico, and subsequent travels through Central America, Africa, Europe, and Asia meeting artists who integrate their art into daily life, Scott recognized that her family’s creative power belongs to a global continuum.

In 1976, Scott learned the peyote stitch from Muscogee (Creek) artist Sandy Fife Wilson, forever transforming her artistic practice. Scott uses this versatile technique as the engine for her art by improvising flat and dimensional beadwork patterns in any shape she can imagine. Scott speaks of her “passport of needle and thread” as a way to connect with people across cultures wherever she goes. She has nurtured deep roots in Baltimore, bringing the world back to her hometown and sharing Baltimore with the world.

“My parents gave me the ability to be a global citizen, and that’s what I was going to be,” says Scott.

Healing, Humor, and Community

Scott’s calls for social justice— an essential component of her artistry—challenge inequality and agitate for freedom. She uses beauty and humor in her works to ignite conversations and draw attention to global and local injustices. Creating a sense of intimacy and deep empathy in even her most confrontational and demanding art, Scott shows that a life of art is an act of resistance and persistence. The Museum offers a conversation guide with prompts and questions to support close looking and processing tough subjects together with young visitors in your care.

Scott uses humor—especially satire—in many of her works as a means of talking about the hurtful consequences of racist stereotypes. In Man Eating Watermelon, 1986, she inverts this racist trope as the beaded sculpture depicts a carnivorous fruit, using this punchline to demonstrate the destructive impact of racist and reductive imagery. The dazzling beadwork and small scale of such works draw viewers in to look more closely and open their hearts to the difficult conversations they spark.

“I believe that art is therapeutic,” Scott explains. “It’s a healing situation.”

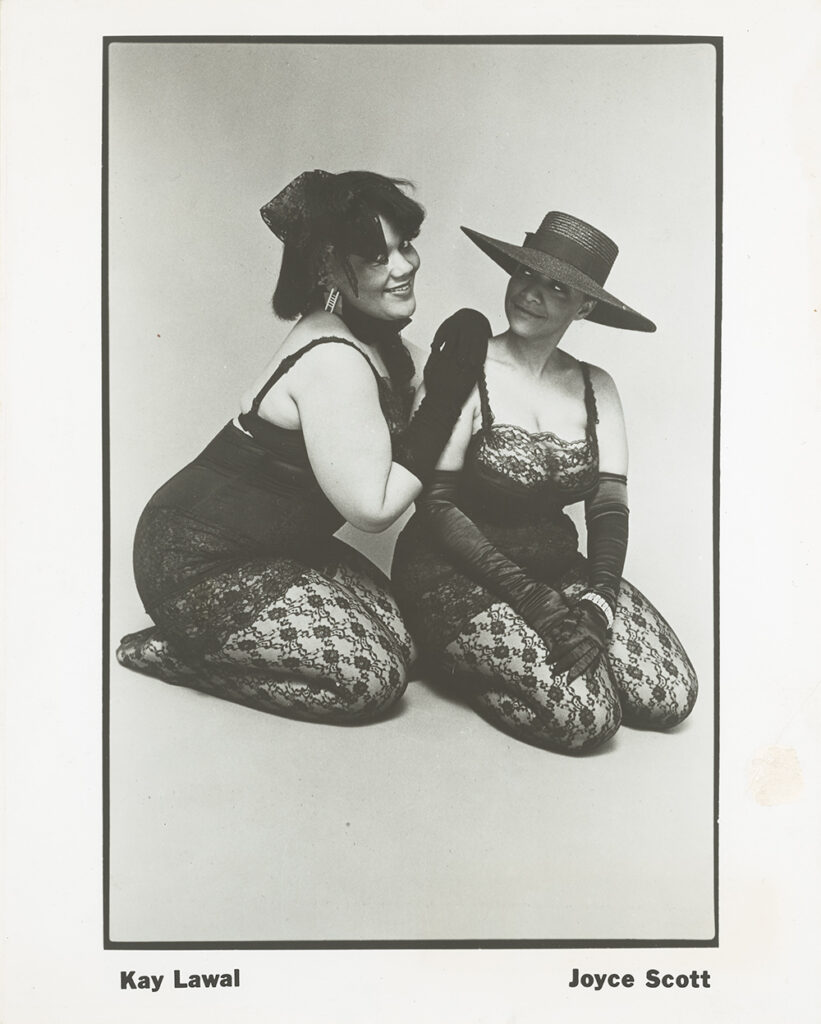

Scott’s use of humor extends to her performance pieces, where laughter is empowering and cathartic. In 1985 Scott and actor/director Kay Lawal-Muhammad created the Thunder Thigh Revue, their body positive performance Women of Substance embracing the full complexity of Black womanhood. The duo toured the United States and internationally until 1990, with a revival show at Theatre Project in Baltimore in 2012.

Identifying as a community artist, Scott’s primary subject is equality shared by all people. Scott remains deeply invested in collective, intergenerational exchange wherever she travels for workshops and residencies and especially in Baltimore, where she has collaborated with the full array of cultural institutions and organizations. Her belief that creation is a communal endeavor may be most apparent in Turning the Tables, the weaving space at the heart of the exhibition.

Here, Scott invites hands-on participation: museumgoers may invoke their own creativity, sit at a loom, and try their hand at weaving. The resulting tapestries will support MICA’s Dr. Joyce J. Scott Scholarship Fund to support artists and designers of color from Baltimore City.

The Threads That Unite

“I luxuriate in beauty. I love just making beautiful things. I know that if my best voice as a citizen is in my work, then that’s what I should be doing.” —Joyce J. Scott

Together, the diverse array of works on view in the retrospective reveal Scott’s indomitable spirit and communal ethos, weaving together communities of artists while honoring ancestral makers, and adorning of the future of art with her wit, wonder, and wisdom.

This exhibition is co-curated by Cecilia Wichmann, BMA Associate Curator of Contemporary Art, and Catharina Manchanda, SAM Jon and Mary Shirley Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, with support from Leslie Rose, Joyce J. Scott Curatorial Research Assistant.

This exhibition and national tour are made possible by substantial grants from the Ford Foundation, Henry Luce Foundation, Terra Foundation for American Art, and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

National Presenting Sponsors

In Baltimore, the exhibition is also supported by the Alvin and Fanny B. Thalheimer Exhibition Endowment Fund, The Dorman/Mazaroff Contemporary Endowment Fund, the Suzanne F. Cohen Exhibition Fund, Bank of America, Wagner Foundation, Joanne Gold and Andrew Stern, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Foundation, Transamerica, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Clair Zamoiski Segal and Thomas H. Segal Contemporary Art Endowment Fund, Goya Contemporary Gallery and Martha Macks-Kahn, The Coby Foundation, Ltd., and the American Craft Council.